|

Listen to article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Canonical texts describing the plan of the Hindu temple allude to its astronomical basis. In this, the Indian sacred geometry is not different in conception from the sacred geometry of other ancient cultures, although it has its own unique features. If astronomical alignments characterize the ancient temples of megalithic Europe, Egyptians, Maya, Aztecs, and Javanese, they also characterize Indian temples. In some specific Hindu temples, the garbhagrÅha (innermost chamber) is illuminated by the setting sun only on a specific day of the year, or the temple may deviate from the canonical east-west axis and be aligned with a nakshatra (constellation) that has astrological significance for the patron or for the chosen deity of the temple.

The astronomy of the temple provides clues relevant not only to the architecture but also to the time when it was built.

A part of the astronomical knowledge coded in the temple lay-out and form is traditional, while the rest may relate to the times when the temple was erected. The astronomy of the temple provides clues relevant not only to the architecture but also to the time when it was built.

In this article, we consider the broadest design related to the sacred space associated with the Hindu temple. There is continuity in Indian architecture that goes back to the Harappan period of the 3rdmillennium B.C.E., as described in Michel Danino’s important work on the plan for the Harappan city of Dholavira. For this reason, we devote our attention to the earliest description of the temple in Indian literature, which goes back to the Vedic period.

Specifically, we look at the astronomical significance of the lengths of the axis and the perimeter of a temple. Since sacred architecture often served as model followed in the design of cities (this is described, for example, by Volwahsen in his book Cosmic Architecture in India) this question is of much relevance. The astronomical basis, however, appears not to have been made note of in relatively recent temple architecture texts from India.

Ritual and Plan of the Temple

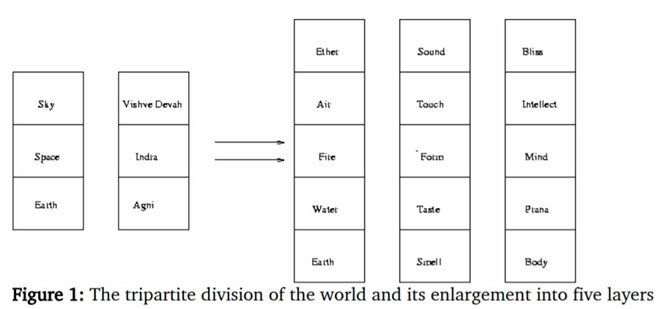

The Agnicayana altar, the centre of the great ritual of the Vedic times that forms a major portion of the narrative of the Yajurveda, is generally seen as the prototype of the Hindu temple and of the Indian tradition of architecture (Vāstu). The altar is first built of 1,000 bricks in five layers (that symbolically represent the five divisions of the year, the five physical elements, as well as five senses) to specific designs. The Agnicayana ritual is based upon the Vedic division of the universe into three parts of the earth, atmosphere, and sky (Figure 1), that are assigned numbers 21, 78, and 261, respectively; these numbers add up to 360, which is a symbolic representation of the year. These triples are seen in all reality, and they enlarge to five elements and five senses in a further emanation.

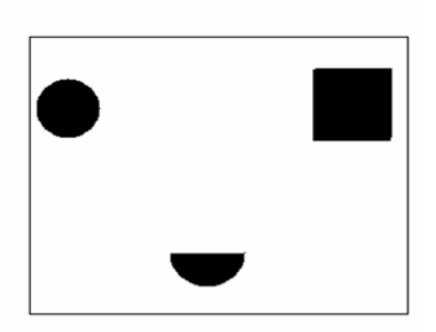

The householder had three altars of circular (earth), half-moon (atmosphere), and square (sky) at his home (Figure 2), which are like the head, the heart, and the body of the Cosmic Man (purusa). In the Agnicayana ritual, the atmosphere and the sky altars are built afresh in a great ceremony to the east. The numerical mapping is maintained by placement of 21 pebbles around the earth altar, sets of 13 pebbles around each of the 6 dhisnya (atmosphere for 13×6=78) altars, and 261 pebbles around the great new sky altar called the Uttara-vedi.

The Agnicayana altar, the centre of the great ritual of the Vedic times that forms a major portion of the narrative of the Yajurveda, is generally seen as the prototype of the Hindu temple and of the Indian tradition of architecture (Vāstu).

The Uttara-vedi is equivalent to the actual temple structure. Vāstu is the remainder that belongs to Rudra, and Vāstupurusa, the temple platform, is where the gods reside, facing the central square, the Brahmasthāna. Given the recursive nature of Vedic cosmology, it turns out that the Uttara-vedi also symbolized the patron in whose name the ritual is being performed, as well as purusa and the cosmos.

The underlying bases of the Vedic representation and ceremony are the notions of bandhu (equivalence or binding between the outer and the inner), yajña (transformation), and paroksa(paradox). To represent two more layers of reality beyond the purely objective, a sixth layer of bricks that includes the hollow svayamātarna brick with an image of the golden purusa inside is made, some gold chips scattered and the fire place, which constitutes the seventh layer (ŚB 10.1.3.7).

The underlying bases of the Vedic representation and ceremony are the notions of bandhu (equivalence or binding between the outer and the inner), yajña (transformation), and paroksa (paradox).

The five layers are taken to be equivalent to the Soma, the Rājasya, the Vājapeya, the Asvamedha, and the Agnisava rites. The two layers beyond denote completion since seven is a measure of the whole. The meaning of this is that the ceremonies of the great altar subsume all ritual.

In the building of the Uttara-vedi, seven special krttikā bricks together with asadhā, which is the eighth, are employed. The firepan (ukhā), which symbolizes Śakti, the womb of all creation, is taken to constitute the ninth. Nine represents completion (as well renewal, as in the very meaning of the Sanskrit word for nine, nava, or “new”) and symbolizes the power of the Goddess. In later representation, which continues this early conception, the nine triangles of the Śri-Cakra represent Prakrti (as a three-fold recursive expansion of the triples of earth, atmosphere, and the sky).

To continue in Part II

Good Information

Good