|

Listen to article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

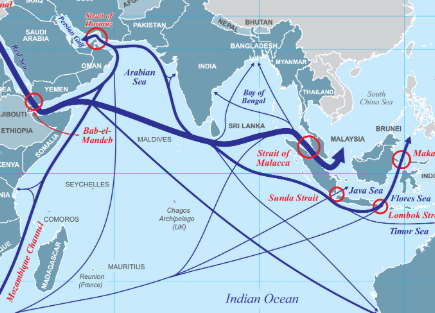

Home to major Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOCs) and strategic choke points of major economies, the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) has gained importance as a major power projection arena over the last few decades. Today, the Indian Ocean is one of the most critical and busiest naval transportation links in the world. Almost a hundred thousand ships pass through it in a year, carrying about half of the world’s container shipments, one-third of the world’s bulk cargo traffic and two-thirds of the oil shipments. The Indian Ocean clearly holds the key to the Asian century which has assumed its name because of significantly growing very large Asian economies. Indian Ocean can thus colloquially be called the centre of the world.

While the attention of other countries towards the IOR is fairly recent, India has maintained trade and civilisational links with many countries in the region long before it was a colonial lake. It is because of India’s unique geographic location and historical, economic and cultural links that make it the pivot of the Indian Ocean. In the present as well India assumes a significant role in the IOR which is also endorsed by the US, Japan, Germany, France and Australia, among others.

India has always believed in the principle of mutual and inclusive growth in a secure environment while staying away from joining any alliance or treaty. Towards the IOR and immediate littoral neighbourhood, this Indian outlook is evident from its vision ‘SAGAR’ (Hindi for ‘sea’) which stands for Security And Growth for All in the Region, and was underlined by the present Prime Minister in March 2015 at Mauritius. It aims at safeguarding the organic unity of the region while advancing cooperation and meeting the challenges such as maritime terrorism, piracy, drug trafficking etc. This vision depends on securing end-to-end supply chains in the region; no disproportionate dependence on a single country; and ensuring prosperity for all stakeholder nations. India’s Indo-Pacific policy is an extension of its SAGAR vision combined with Act East policy which are guided by norms and governed by rules, with freedom of navigation, open connectivity, and respect for sovereignty of all states.

Over the current period, with increasing globalisation, trade dependence, the seamless connectivity of the maritime domain and the changing nature of the maritime threat becoming more transnational in nature, physical boundaries have become blurred and awareness of the importance of ensuring secure seas for the unhindered movement of trade and energy has increased. This has also coincided with the remarkable and historically unprecedented rise of China, in sheer scale and ambition. Its territorial claims in the South China Sea, belligerence in the East China Sea and rapid advance into the Indian Ocean through ambitious strategic and economic initiatives like the Belt-and-Road Initiative (BRI) have challenged the established international rules-based system which respected the oceans as the common heritage of mankind.

With this background in mind, it is easy to conceive how the Pacific Ocean region has expanded (theoretically and geo-politically) to become the Indo-Pacific region. The significance of Indo-Pacific today has its roots in the Indian Ocean becoming the crossroads of global commerce on the one hand and an arena of emerging power-based competition on the other. The threat to a rule-based world order in the oceans of this region became the primary reason for the convergence of major stake-holding democracies. Hence a Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) became significant though the quotient of ‘security’ from QUAD is still being underplayed.

Before the emergence of Indo-Pacific concept, India was already strengthening security and freedom of navigation in the IOR and handling responsibilities of a regional security provider – for instance participating in peacekeeping efforts or anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden. By sharing equipment, training and exercises, India has built relationships with partner countries across the region. In the past few years, India has provided coastal surveillance radar systems to half a dozen nations – Mauritius, Seychelles, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Myanmar and Bangladesh. All of these countries also use Indian patrol boats, as do Mozambique and Tanzania. The frequency and number of defence training programmes have also increased. Mobile training teams have been deputed to 11 countries – from Vietnam to South Africa, as well as Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Myanmar. India has been actively engaging regional as well as extra-regional countries in international defence exercises on bilateral and multilateral platforms. The recently concluded Exercise Desert Knight 2021 is one of the examples of strategic engagements. It was a bilateral exercise between the Indian Air Force and the French Air and Space Force, conducted in the western sector of India. This hints at global appreciation of Indian Armed Forces and enthusiasm about engaging them for mutual understanding of operations.

There are several examples of India extending help in neighbourhood and beyond in the form of many Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) missions and evacuation operations. Besides providing succour in many natural disasters like tsunamis, cyclones and earthquakes, India has extended help to more than 150 countries in the ongoing pandemic in form of medical supplies. By giving millions of indigenous vaccines for COVID 19 to friendly countries, India is enhancing its soft power footprint in the world. India has already sent 3.2 million free doses of the vaccine Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives. Seychelles, Mauritius, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Afghanistan also are likely to get free Indian vaccines soon. Far from the IOR, India on 22 Jan sent two million doses of the vaccine to Brazil as well.

With the latest change of the US leadership, it is being assumed that QUAD- the most powerful association to oppose Chinese hegemony is in the doldrums. India must continue engaging regional democracies on bi-lateral, tri-lateral or multilateral basis while focusing on IOR as well as strategic partners. Even if the QUAD goes back to the back-burner it must take the lead to preserve the rule-based world order in its area of responsibility i.e. the Indo-Pacific. Just as the centrality of the ASEAN to the Indo-Pacific cannot be overlooked, the centrality of India to the Indian Ocean too cannot be underplayed. If the Indian Ocean can now be called the centre of the world and India is in the centre of the Indian Ocean, then India has to assume the responsibility for this critical position.

Add comment