|

Listen to article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In the wake of the spread of the Covid-19 epidemic from Wuhan to the rest of the world, continuing armed stalemate at the unsettled borders, and of India’s refusal to join the China-centric Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, the economic and trade relations between India and China are expected to undergo substantial changes in the short term to medium term.

India was rudely jolted this year by the twin disasters of Covid-19 that sapped its economy (due to extensive lockdowns) and the armed intrusion of China’s military across the borders. China is yet to explain to the Indian people why it chose to hit India on its border at this time. This has vitiated the bilateral relations, including economic relations.

First, due to Covid-19 disruptions in supply chain mechanisms caused by lockdowns, social distancing norms and decline in demand patterns, manufacturing, services and trade came to a standstill, except in health-related products. The World Bank estimated to a 5.3 percent decline in growth rates across the globe, with over $8.2 trillions being wiped out in the total GDP. The World Trade Organisation detected a double-digit decline in trade, while the International Monetary Fund cautioned about global debt increasing to more than $2.5 trillion. The overall economic decline impacted the bilateral economic and trade relations between India and China.

Covid-19 and the skirmishes at the border are frittering away decades of work done to promote trade and institutional arrangements between the two countries. In 1984 a most favoured nation status was signed followed a decade later in 1994 by a Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement. Later, after the Bangkok Agreement was signed, both extended trade concessions – with India providing tariff concessions to 188 products imported from China, while China preferring 217 Indian products. Later, “financial dialogues”, “steel dialogue”, CEO Forum, Strategic Economic Dialogues commenced. As a result, bilateral trade figures which were negligible in 1991 at $264 million increased to $2.32 billion in 2000, $18 billion in 2005, $ 74 billion in 2011, $66 billion in 2012 and $65.47 billion in 2013. The 2005 target of reaching $100 billion by 2010, however, was never met. According to Indian Ministry of Commerce statistics, while the bilateral trade volume stood at $81.8 billion in 2019, by September 2020 the figure came down to $37 billion, while China’s corresponding customs statistics show $92.9 billion and $60.5 billion respectively.

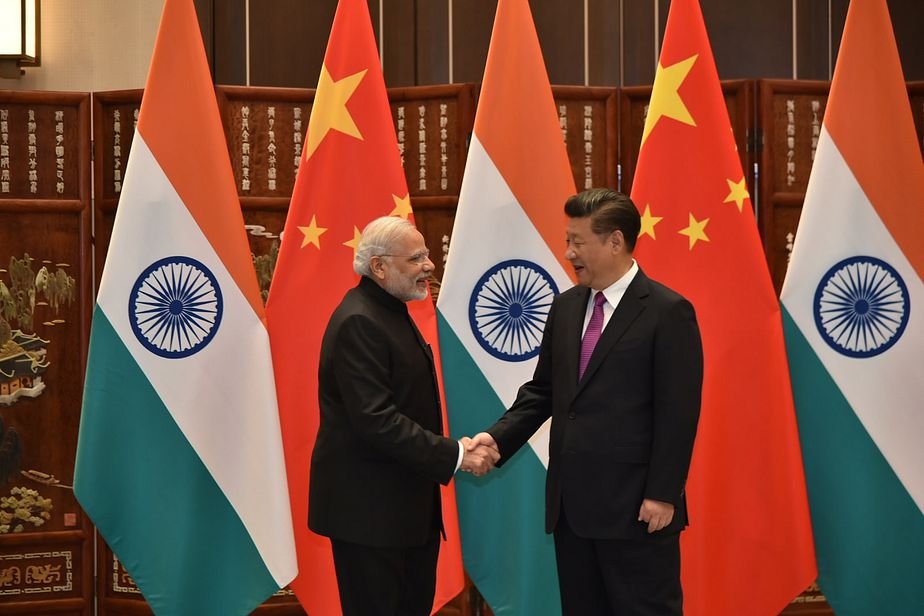

Secondly, related to the above, the rising trade deficit has become a contentious issue between the two. China’s exports to India increased over a period of time while its imports from India have been much lower in value, owing to non-tariff barriers, lack of bulk and spot purchases and investments, currency manipulation, lack of market economy status and other factors. Cumulatively, in the last decade, India’s trade deficit with China amounted to more than $850 billion in favour of China. This was raised at the highest levels by the Indian leadership, first by the then President Patil during her visit to Beijing in mid-2010. Subsequently, successive Indian Prime Ministers had mentioned this explicitly with their Chinese counterparts. India is demanding market economy status in China as Indian products – specifically pharmaceutical and software – are discriminated against on the Chinese market. Finally, at the Wuhan informal summit meeting between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping in April 2018, it was resolved to address this issue by allowing 29 pharma products into the China market. Since then however, there has been only marginal improvement in Indian exports to China.

Thirdly, much of the above trade is in the maritime domain, while cross-border commercial exchanges remained negligible – primarily because the border dispute remained unresolved. In 1954, when India recognized Chinese sovereignty over Tibet, a trade agreement was also signed between the two countries for eight years. However, following the onset of chill in the bilateral relations from the late 1950s, this trade treaty was not ratified, affecting drastically the economies of the traditional border trade posts. Though border trade existed between the two countries for centuries, it came to a standstill after the 1962 war, only to resume in the 1990s. Since then border trade was allowed, with several caveats, from Shipki La, Lipu Lekh and Nathu La and is estimated at over $100 million annually. Current tensions following the Galvan incident are expected to further reduce border trade, negatively affecting traditional households in the trans-Himalayan belt.

Fourthly, while one way of reducing the negative effects of trade deficit is through mutual investments, specifically from China, this is an area of negative or negligible growth. It is is surprising since both China and India, simultaneously rising great powers in Asia have received substantial foreign direct investment flows in the past decade. China is one of the largest such destinations, which greatly account for its rapid economic growth. India has also jumped phenomenally in ease of doing business recently and its over $1 trillion plan for infrastructure development is attracting considerable attention. However, mutual such investments between them have been paltry. During President Xi Jinping’s visit in September 2014, it was announced that $20 billion would be ploughed during the following five years in India’s manufacturing zones, while Prime Minister Modi’s visit in 2015 to Beijing and Shanghai led to promises by the Chinese businesses amounting to over $32 billion. However, official statistics from China suggest that the cumulative investment from China in India is about $8.2 billion, with an alarming proportion in unicorns in the last two years. India has been growing between 5 to 8 percent in the last two decades. Yet China finds the Indian market less attractive than turbulent Pakistan. This suggests China has strategic considerations rather than markets in mind while investing abroad.

Fifthly, long-term and large-scale economic relations have been a casualty of Beijing’s stubborn attitude in the border conflict. An India-China free trade agreement (FTA) could transform bilateral relations substantially – making this the largest FTA in the world in terms of volume and turnover. The Joint Study Group set up during Indian Prime Minister’s visit to China in June 2003, had recommended forming a bilateral Joint Task Force to look into the feasibility and benefits of a regional trade agreement (RTA) with China. The task force met several times but soon differences cropped on the “mutually advantageous” clause. China’s intransigence about opening up its market, reducing debilitating trade deficits, relaxing import restrictions and removing barriers and others not only led to aborting the FTA project but also derailed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) discussions. After seven years of negotiations since 2013, India skipped joining the 15-member RCEP citing tariff differential changes, ratchet provisions on investments, goods of origin and the problems of currency manipulation, impact on livelihoods, equity and balance principles. Besides, India already has FTA or other such arrangements with 11 out of the 15 members.

Thanks sir for in-depth and enlightening research on this burning topic.