|

Listen to article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In my earlier piece titled- Introduction to Indian Temple Architecture, I delved into the fundamentals of the two prominent styles, Nagara and Dravida, of temple architecture in India. In the second article of the series, titled Introduction to Nagara Temple Architecture, I wrote on the north Indian style of temple architecture with reference to its various mentions in the architectural treatises. This article will focus on the South Indian style of temple architecture also referred to as the Dravida style.

The earliest specimens of Dravida tradition are present in the form of brick shrines in Ter, Maharashtra and Chezarla, Andhra Pradesh.

Under the constant cultural influx from north India, the south Indian temple architecture evolved out of the pre-existing secular architecture prevalent in the region. The earliest specimens of Dravidatradition are present in the form of brick shrines in Ter, Maharashtra and Chezarla, Andhra Pradesh.Both were Buddhist sites, most probably Chaitya halls later converted into Hindu shrines. These shrines feature apsidal types of Alpa-vimana crowned by a barrel roof Shala covering and they are dated around the 3rd to 4th century CE.

The most important feature of the Dravida style is that its superstructure is always in the shape of a stepped pyramid where all its tiers are strongly visible; rather each tier is decorated with a combination of Kuta, Panjara and Shala at intervals that distinguish the tiers.

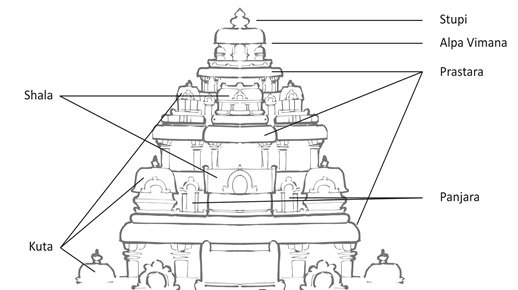

Unlike the Nagara tradition, the Dravida style doesn’t allow for variety in the Shikhara typologies in general. The Dravida style was codified with fixed components. Under this, we see a completely different form of temple architecture which is nothing but a combination of Alpa vimana, Kuta, Shala and Panjara (refer the figure below). The Dravida style incorporates all these elements in a temple arranging them from top to bottom on an increasing scale. The most important feature of the Dravida style is that its superstructure is always in the shape of a stepped pyramid where all its tiers are strongly visible; rather each tier is decorated with a combination of Kuta, Panjara and Shala at intervals that distinguish the tiers. The walls of the Dravida temple always have pillar-couplets at intervals. However, this rule wasn’t followed in every structure. Sometimes a niche or aedicule was carved in between those coupled pillars in order to place a sculpture within.

We see variations in the heights and details of the fixed superstructural elements. However, we do see some different types of roof forms in the famous rock-cut Pancharathas at Mahabalipuram carved out under the Pallava dynasty most probably in mid-7th CE or earlier. These types of roof forms can be basically assigned to the early form of Dravida temple architecture. Texts like Mansara, Mayamatam and Kashyapa Shilpa talk about the Dravida style in greater detail.

Pancharathas of Mahabalipuram

The Draupadi Ratha, the smallest of all, has a square plan with a hut shaped roof known as Kuta. The temple has simple wall projections without any intricate mouldings.

The Arjuna Ratha, which is on the same platform, has a square plan with a Garbhagriha and a small Mukhamandapa attached to it. The roof form is complex as compared to Draupadi Ratha. It is aDvitala or two-tiered Shikhara adorned with a Vimanam and elements like Kuta, Shala and Panjara.

The Bhima Ratha is a long rectangular shrine with an Ektala barrelled roof or Shala Shikhara. The presence of ornate columns on all sides gives a sense of circumambulation path within of Sandharaplan. The Nakula-Sahadev Ratha is a different type of monolithic shrine with a Gajaprishtha roof; shaped like an elephant back adorned with two ornate columns.

The Dharmaraja Ratha is the most exquisite of all the Rathas. The shrine has a square floor plan within a rectangular frame. It has an open porch supported by pillars. It’s a Tritala or three-tiered Shikharawith a Vimana at the top further adorned with the Kuta, Shala and Panjara in a succession.

After the power shift from Pallavas to Cholas in the 9th CE the Dravida temple construction took a leap in scale especially during the reign of Raja-Raja Chola. The majestic temple of Brihadeeshwara at Thanjavur surpassed all the records set by previous temples. Built-in the 11th CE it has the tallest Vimana with fourteen Talas or tiers and the Adhisthana has two Kostha, doubling the height of the inner sanctum. All the fourteen Talas are adorned with Kuta, Shala and Panjara as seen in otherDravidian sanctuaries. The other two temples named after Brihadeeshwara at Gangaikondacholapuram and Airavateshwar at Darasuram are even more ornate but do not surpass the mammoth proportions of the original one situated at Thanjavur.

The relative immunity from foreign invasions in the south, when compared to northern India, has clearly resulted in the preservation of the ancestral Dravida style.

These few examples from South India show how rituals and beliefs have shaped public spaces in the form of temples. The relative immunity from foreign invasions in the south, when compared to northern India, has clearly resulted in the preservation of the ancestral Dravida style. The vast panorama of Dravidian temples still in existence especially in the present-day states of Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu is made famous by iconic sanctuaries built during eras of the Pallavas, Chalukyas, Cholas, Pandayas, Kakatiyas and others. The recent destruction of historic pillars at the Vijaya Vitthala Temple, Hampi must steel us to intensify our efforts for the preservation of these ancient sites which hold the key to the knowledge and traditions of our glorious past.

Add comment