|

Listen to article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

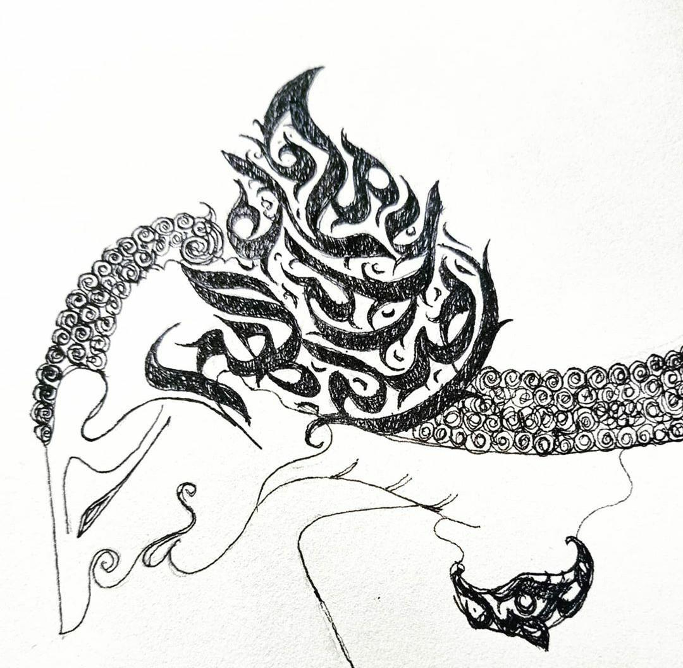

In December 2018, the President of Indonesia, Joko Widodo (commonly known as Jokowi) met with several artists, masters and cultural practitioners to discuss the national cultural outlook for Indonesia in the years to come. During the meeting, Jokowi decided to declare November 7th as National Wayang Day to strengthen Indonesia’s commitment to traditional values and the civilizational heritage left by the ancestors. Wayang is a shadow puppet theatrical art form based on the stories of Mahabharata and Ramayana with some local modifications. As a performing art, it is usually played all night with a Dalang (puppeteer) and groups of musicians. Wayang was chosen to be the focal point for the commemoration of Indonesia’s cultural heritage as it has a broad appeal among many Indonesians, especially in Java. Wayang was also selected as a part of the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Indonesia back in 2003.

During the 1st anniversary of National Wayang Day in 2019, several events were held to celebrate the tradition. In provinces of West Java, Central Java and East Java, Wayang performances were staged all night by various shadow puppet masters and their accompanying musicians. Many of these Wayang performances were sponsored by government officials as well as cultural organizations and were attended by large audiences composed of youngsters.

This phenomenon brings us to an essential question: how did the Wayang tradition survive and become more popular in the 21st century despite the domination of instant and on-the-go entertainment like Netflix and YouTube?

Keys to Survival: Cultural Politics and Quasi-Theistic Secular System in Indonesia

Despite being a Muslim-majority county, Indonesia has adopted a policy that ensures respect and protection of various cultural identities that are living and existing within the boundaries of Indonesia. This policy is particularly enshrined in the five pillars of the Republic of Indonesia, which are called Pancasila. When the first President of Indonesia, Soekarno elaborated the dictum of Pancasila, he said that Indonesia should be a nation that unifies different religious and cultural affinities. Sukarno emphasized that spiritual life in Indonesia should not be detached from its cultural and civilizational elements.

Thus, an Indonesian Muslim could follow Islamic religious laws and obligations while also preserving his roots stretching back to the era of Hindu-Buddhist civilization. Sukarno coined this concept in the term of Ketuhanan yang Berkebudayaan or civilized religiosity/theism with culture. Sukarno thought that the idea of civilized religiosity should eradicate any feelings of ‘religious egoism’ amongst religious believers in Indonesia. This kind of understanding developed by Sukarno was rooted in a long tradition of Muslims in Indonesia, who always regarded the cultural and civilizational heritage from Hindu-Buddhist ancestors as being integral to their life as an Indonesian Muslim. Several early Muslim preachers in Indonesia had used parts of the Indic lore to spread the message of Islam.

The traces combining the Hindu-Buddhist legacy and Islamic teaching can still be seen in the plays of Wayang Sadat, in which a Muslim preacher teaches moral values by combining the Islamic texts of Quran and Hadith with the teachings of Mahabharata and Ramayana.

Sukarno’s thought was reiterated by Abdurrahman Wahid, who once held the office of the presidency of Jam’iyyah Nahdlatul Ulama (the largest Islamic congregation in Indonesia) and the presidency of the Republic of Indonesia. According to Abdurrahman Wahid, the understanding of Islam in Indonesia should be based upon the respect of local wisdom. It should carry the legacy of ancestral beliefs rather than kneeling under the project of “Arabization” in Indonesia.

Another aspect that contributed to the continuing practice of multiculturalism in Indonesia is that Indonesia implemented a softer version of secularism. Scholar Al Khanif has said that Indonesian understanding of secularism could be defined as a “quasi-theistic secular system”, in which the state acknowledges the role of religion in the public sphere but does not recognize the privilege of a particular religion. This system is enshrined as one of the main pillars of Pancasila, which states that Indonesia would never be founded upon a specific religious philosophy or religious law.

Mahabharata and Ramayana as a Re-Imagination of Indonesia and an Allegory of the Present

The texts of Mahabharata and Ramayana have been circulated in Indonesia since the 10th century A.D at least. The ascent of Islam in Indonesia could not make the influence of Mahabharata and Ramayana fade. The hallowed epicsparticularly survived due to their usage as political philosophy and political allegory by Indonesia’s political leaders who were prominently Muslim. The first president of Indonesia, Sukarno, used the battle of Bharata Yudha as an allegory of the political crisis that he faced after the coup attempt directed at him in October 1965. He also took an example of the state of Uttarakuru as one of the parts of Ramayana during his Maulid-un-Nabi speech in 1964. He said that Indonesians should not be merely satisfied with the comfort of Uttarakuru and struggle to become a better nation instead.

This tradition continued especially under Suharto, the second president of Indonesia who was a firm believer in Javanese traditions. Suharto used Wayang as a political tool to establish his legitimacy, particularly amongst the majority Javanese populace. Suharto asked Dalangs to carefully convey the message of national development through allegories and artistic performances in order to influence people’s minds. In the years up until the last years of his regime, Suharto supported and sponsored many Wayang performers.

Currently, the usage of Mahabharata and Ramayana for political allegory remains prevalent. Recently, many memes have been in circulation to compare the political contestation between Joko Widodo and Prabowo Subianto (previously an opponent to Joko Widodo, now Indonesian Minister of Defense) with the conflict between Pandavas and Kauravas. These political allegories can also be seen in many other examples such as in the use of Ravana to characterize disliked political figures in Indonesia.

Indonesia has been successful in defending its credential as a ‘multicultural’ and ‘quasi-theistic secular nation’ in an atmosphere of rising religious radicalism and anti-democratic forces across the world. In its efforts to strengthen this credential, the Indonesian political establishment, as well as its people, find relevance in references to the cultural past in the context of the present. The cultural and historical roots continue to sustain a common ground for the diverse Indonesian nation.

This article is written in memory of late Ki Seno Nugroho, one of the most famous Dalangs (shadow puppet masters) in Indonesia who recently passed away and also to commemorate the National Wayang Day celebrated every November 7th.

Add comment