|

Listen to article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The 14th BRICS Summit, chaired by China, was organised virtually from June 23-24 on the theme, “Foster High-quality BRICS Partnership, Usher in a New Era of Global Development,” in the backdrop of the challenges launched at the world by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, propelling a crisis in hydrocarbons, food, and living costs, threatening to derail the post-pandemic recovery of emerging economies. The summit was preceded by the meeting of the NSAs a week ago, where the activeness of the BRICS Counter-Terrorism Working Group was emphasised. India’s NSA posited an expansion of the notion of national security to impart agility to supply chains and a safe outer space. Ironically, China blocked India and America’s bid to label the Lashkar leader Abdul Rehman Makki as a terrorist in the UN Security Council’s Al-Qaeda and ISIL Sanctions Committee, a day later.

The Summit commenced with the opening ceremony of the BRICS Business Forum on June 23, followed by the addresses of the Heads of State. President Xi Jinping subtly cautioned the West against the isolation of Russia, accusing them of imposing “deliberate disruptions” in supply chains, and situated the BRICS as a torchbearer of multilateralism opposed to the “power politics” of Cold War schemas. President Putin decried the closed economic system being promoted by Europe and North America, and criticised their unsustainable monetary policies; he urged the attending leaders to link their currencies to the Russian Financial Messaging System, a retort to Russia’s banishment from the SWIFT. PM Modi’s address skirted past these issues, rather concentrating on India’s technology and innovation-centric reforms and financial inclusion, and lauding civil society organisations. South Africa’s President Ramaphosa underscored the expansion of access of developing countries to goods and services, especially medical supplies, while President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, laid stress on economic integration for “mutual gains,” and reforms in the UN system and IFIs.

Implications

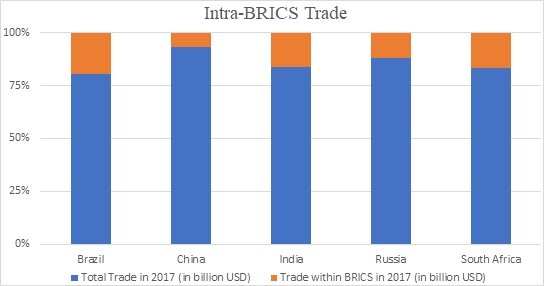

The Chinese media, notorious for its grandiose hyperbole went to great lengths to outline the potentiality of transformation in global governance through the mechanisms perfected by the grouping. Under this veneer, however, fault lines are continually expanding. The insecurity of Russia did not wean itself off the minds of the participants: the document was reticent on the topical concern of the war in Ukraine. The grouping’s solidarity with Ukraine was clubbed with the equally topical problems of the Middle East and North Africa, Iran, Korea, and Afghanistan. The declaration made substantial references to initiatives on the digital economy, intra-BRICS trade, finance, and the contingent reserve arrangements (CRAs) for monetary discipline.

Unarguably, China’s ink was strewn on the entire event—from its overarching theme to the Beijing Declaration. If the Beijing Declaration and Chairman Xi’s speeches were rich in attention to the development and a green transition, it is perhaps attributable to the launch of a new flagship, the Global Development Initiative (GDI), announced in the UNGA in 2021. Like the BRI, the GDI is deliberately vague, though it alludes to China’s commitment to Sustainable Development Goals—a novelty given that much of the BRI is founded on the essentials of the Chinese growth story: concrete, steel, and coal. Detractors, though, have cautioned that the GDI will be no more recipient-centric and inclusive than the BRI, and may compound the political and financial bind the developing world finds itself in.

But China’s vision, and its propagation through the forum of BRICS, send a belated message to the Global South. The low and middle-income economies on its radar have more options for attaining official development assistance (ODA) than they had in 2013 when the BRI discourse originated at Astana. This includes, but is not limited to, the Build Back Better World initiative announced during the G7 summit in Cornwall; the Blue Dot Network of Australia, Japan, and the US; and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity. The late realisation among liberal democracies to plug the deficit of development financing in Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific was exploited assiduously by an ascendant China before its so-called “debt-trap diplomacy” tightened brows and imparted a new opening to what had become their sequestered narrative.

China’s failure begins to hit harder when the manner of the summit’s conduct comes under the spotlight. There was no perceptible reason for holding the meeting virtually, except one: strained relations between India and China, providing a glaring testimony to the outstanding fissures of this grouping. Since the Galwan clash, the worst flare-up in Sino-Indian tensions in 5 decades, in 2020, relations between the two nuclear powers have been frosty to an extent that economic relations between the two, which they’d adroitly decoupled from territorial and political disputes, imploded, as India imposed restrictions on Chinese investment and commerce.

The fissures in the BRICS threaten to make the grouping ineffectual in practice. On June 26, India and South Africa will be attending the G7 summit with other states in the Global South, including Indonesia and Senegal. Attendance in Schlauss Elmau would ensure articulation of India’s and the Global South’s views on climate change and green transition, post-pandemic economic recovery, and the war in Ukraine. Furthermore, Indonesia and India are slated to successively hold the presidency of G20 in 2022 and 2023 respectively—a grouping more readily associated with multilateralism due to its diversity and brighter economic outlook, a veritable constellation of regional powers and emerging economies working with the industrialised countries.

Wang Yi’s surprise visit to New Delhi in March was a last-ditch attempt to secure India’s physical participation in the Summit. He had to console with a virtual summit since he didn’t bring a concrete set of measures for disengagement in Eastern Ladakh; India has been determined to not decouple disengagement with other contours of its relationship. For China, it was important that India attend the conference in the physical format, as India’s absence would in all likelihood have resulted in the other BRICS countries too, being reluctant to attend in the physical format, the diplomatic fallout of the same being unsettling for Beijing, largely because it has fashioned the BRICS as the primary platform for advocacy of the issues of the Global South. The success of China’s outreach to the Global South and its foreign policy are, thus, coterminous, and crucial to Xi Jinping when he faces the 20th National Congress of the CCP.

Looking Ahead

To stay relevant, the BRICS needs to expand, lest it becomes an elitist congregation it fervently avoids being. Rumours were rife that India will seek to block such an attempt; however, it seems unlikely. After all, India has welcomed Bangladesh, the UAE, Egypt, and Paraguay into the New Development Bank, where the 5 BRICS countries have an equal vote; and the 14th summit registered the presence of developing countries like Indonesia and Cambodia. Nevertheless, India will take umbrage with unilateral decision-making in the grouping’s expansion, which will inevitably broaden Chinese clout, making it first among equals.

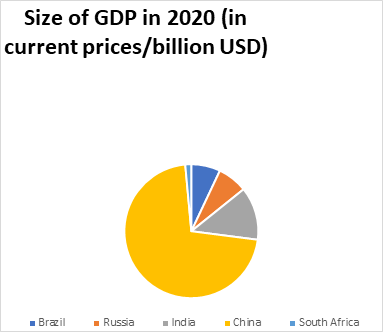

BRICS started as a reformist grouping of countries sharing complementarities: in a famous extrapolation, Brazil serves as the grouping’s agricultural powerhouse; Russia an energy superpower; China as its manufacturing hub; India as a service provider; and South Africa a mineral base. But lately, and unsurprisingly, its functioning has become loudly geopolitical. Elsewhere, it may be a welcome symptom of vibrancy, but here, the penetration of geopolitics threatens to pull the members apart. India, South Africa, and Brazil have been desirous of reforms in the UNSC to stake claim to a greater, deserved share of the political pie; the occupants of the permanent seats are expectedly status quoist. China and Russia are inclined to create a shadow international financial architecture and reserve currency (arguably the Renminbi); China, more aggressive and endowed, has created the Chinese Exim Bank and AIIB in this vein. However, the other three powers have profited from liberalisation and free trade to varying, though undeniable extents, and their advocacy of reforms mustn’t be interpreted as forsaking the USD, WTO, and IFIs. In fact, it is widely believed that India ensured that the summit and its Beijing Declaration do not become tools of anti-American and anti-EU propaganda.

Nevertheless, the oft-repeated statistics become more consequential: BRICS accounts for 40% of the global population, 25% of GDP, and 40% of the land. But it needs to explore convergences beyond reforms in the international economic and financial architecture, where the five countries seldom concur. For instance, it can expand its share of world trade, as well as intra-BRICS trade, which amounts to a paltry 10.61%. The BRICS’s proponent rued that barring China—which, despite its demographic challenges and zero-covid policy, grew at 4.8% in Q1 of FY22—and India—back at being the fastest-growing major economy whose growth is slated to exceed 7% in FY22—every major economy has disappointed. Russia has become a pariah state, and its hydrocarbon-centric economy will take a hit as the EU plans to diversify its energy basket. Brazil is a classic case of a resource curse and political turmoil, its growth rate languishing around 1%. South Africa’s predicament has been similar, and it has had to continually justify its presence in the BRICS instead of Nigeria’s.

The BRICS, thus, direly needs reforms to remain relevant. Unlike in 2009, when there weren’t many alternatives available to the Global South as there are today, the G20 and BRICS had immediately resembled solutions to the absence of their influence and voice in decision-making. The BRICS needs to expand and accommodate values contrary to China’s. It hasn’t provided enough solutions to pressing problems; the New Development Bank, with its democratic decision-making and active development financing, is an exception whose success must be modelled for future initiatives. While it can represent the developing world—as it has during various ministerials of the WTO and in the form of the BASIC at the CoP15, Copenhagen—it will have to proactively ensure the implementation of international treaties and agreements, e.g., on cutting global GHG emissions, 42% of which come from its members. Lastly, the BRICS is on the verge of degeneration into a talking-shop; to retain primacy in the Global South, it will need to explore, create, and build on existing convergences in multilateral governance.

Add comment