The Leader’s Declaration at the G20 South Africa Summit acknowledged the historical significance of cultural property and its role in strengthening social dialogue at a time of global misappropriation. India’s proposal to establish the G20 Global Traditional Knowledge Repository is a significant step towards protecting the cultural rights of indigenous communities, essential to the realisation of economic progress. The AI revolution poses a risk to indigenous culture and traditional knowledge, particularly in crucial sectors such as agriculture, health, life sciences, and art. India’s experience with protecting indigenous communities and supporting their culture, practices, and traditional knowledge can offer a roadmap to the world.

Cultural Rights and Traditional Knowledge

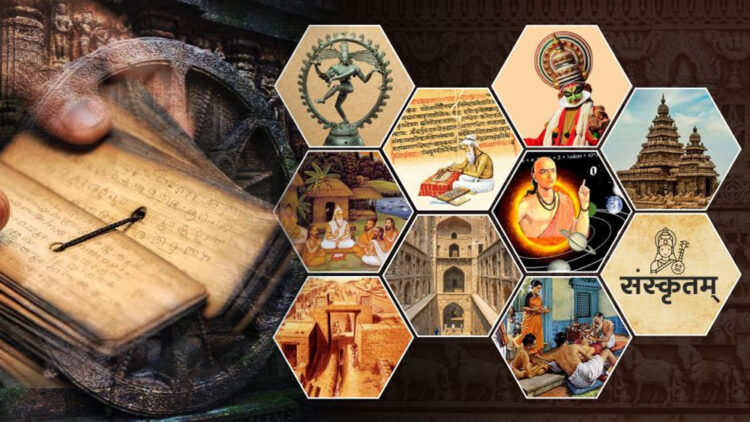

Cultural heritage and traditional knowledge systems occupy a significant place in soft power and economic development. There is no universally accepted definition of Traditional Knowledge (TK). Heritage is an umbrella term inclusive of TK, Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs) and Indigenous Knowledge, often overlapping. TK contributes significantly to India’s GDP through the Agriculture, Health, Life Sciences, Creative and Cultural Heritage, and MSMEs sectors. On the international level, TK is mainly addressed through six international organisations (IOs):

- The International Labour Organisation (ILO)

- The United Nations Commission on Human Rights and the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues

- The World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO)

- The United Nations Educational, Scientific, Cultural Organisation (UNESCO)

- The World Trade Organisation (WTO)

- The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

The World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) has taken steps to protect TK and TCE through defensive and protective measures by preventing outsiders and external agencies from acquiring IP over traditional knowledge, and granting ownership rights to communities. While WIPO exists to protect the IP rights of vulnerable communities, the current structure is Western in its approach and individual-centric.

The Westernisation of the WIPO IP framework can be understood through the relationship between Intellectual Property Rights and Human Rights in a phased manner. During and before the mid-1990s, cultural human rights and IPR existed separately; however, the 1990s saw the beginning of IP protection through multilateralism and national legislations. The first decade of the 21st century saw the emergence of human rights activists focused on cultural rights in the developing world opposing the unilateral expansion of the IP regime by the ;developed’ nations. After 2010 the codification of IP regimes through treaties and litigation influenced the protection of cultural rights. The two major human rights instruments that protect the cultural rights of indigenous communities, particularly in the Global South, are the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and Article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) define Cultural Rights. In simple terms, these rights enable access, participation, and contribution to cultural life as well as accruing benefits from the scientific progression and use of traditional knowledge systems.

While WIPO does not define indigenous peoples, the ICESCR says indigenous people are the original inhabitants of a land with unbroken continuity and a precolonial link with nature, serving as protectors of the traditional knowledge. Civilisational heritage flows through indigenous expressions such as languages, philosophical knowledge, trade, art & craft, and oral traditions. At present, Indian TK formally encompasses Ayurveda, Yoga, Vedic Philosophy, and Mathematics, among other knowledge systems that directly influence the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 2030 Agenda.

Part III of the Indian Constitution, Article 29(1) under the Cultural and Educational Rights guarantees that any section of the citizens residing in any part of the territory of India having a distinct language, script, or culture of its own shall have the right to conserve the same. Additionally, under Section 3p of the Indian Patents Act, 1970, an invention which, in effect, is traditional knowledge or which is an aggregation or duplication of known properties of a traditionally known component or components, is non-patentable. In addition, the Patents Act, 1970 provides for disclosing the source and geographical origin of the biological material in the specification, when used in an invention and conveys the information to NBA, thereby facilitating compliance. To summarise, India’s domestic legal framework empowers indigenous people and protects TK and TCEs.

Southern Imperatives

The challenges to the realisation of cultural rights and protection of TK and TCE are threefold. First, traditional knowledge lacks the appropriate legal protection, contrary to external actors utilising it in inventions or creative work. Second, the indigenous communities are often deprived of their right to enjoy the economic/commercial benefits emanating from their knowledge. Third, most indigenous communities face loss of culture and exploitation of their work. The traditional knowledge is prone to misappropriation for profit motives in more advanced economies without profit sharing with the vulnerable indigenous groups in the Global South and without their consent. Global AI governance may present new challenges to the protection of culture and heritage since the Global South nations are underrepresented in the rule-making bodies and processes, because of their less technologically savvy domestic environments. The AI revolution is significantly increasing the digital and economic divide between Global North and South nations, directly affecting the rights of the most vulnerable communities in the world. A report by the Independent Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence and Culture (CULTAI), convened by UNESCO, underscored how AI has implications for cultural rights and indigenous communities with core challenges such as outpacing of governance, reinforcement of bias and homogenisation of culture as well as erosion of creativity and skills.

From a development perspective, the protection of indigenous rights has a direct correlation with the ability to attract FDI, GDP growth, market activity, and SME Value. The G20 South Africa Declaration mentioned, “We acknowledge the importance attached by the countries of origin to the return or restitution of cultural property that is of fundamental spiritual, historical and cultural value to them so that they may constitute collections representative of their cultural heritage. We reaffirm our support for open and inclusive dialogue on the return and restitution of cultural property, while acknowledging the increased recognition of its value for strengthening social cohesion.” Additionally, the G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration reaffirmed culture as a force for transformation indispensable for the ambitious 2030 SDG Agenda. During India’s G20 Presidency, global leaders committed to combat illicit trafficking of cultural property and to utilise diplomacy and intellectual property rights to protect indigenous communities and cultural practitioners. To add more, the G20 Rio De Janeiro Leaders’ Declaration acknowledged the significance of cultural rights and called for a stronger global cooperation on IPR issues, including the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on the restitution of cultural property of communities and countries of origin.

India, Cultural Rights and Traditional Knowledge

India’s commitment to Cultural Rights and protection of Traditional Knowledge is rooted in its civilisational continuity and the colonial past. In India, Janjatiya Gaurav Divas is celebrated to honour the contribution of indigenous people to national development. In the words of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs,” India’s rich cultural diversity is largely shaped by its tribal communities (indigenous people), who have played a crucial role in the nation’s history and development.” India not only acknowledges the challenges faced by indigenous rights but has also implemented social welfare schemes in areas of education, healthcare, and economic opportunities to preserve indigenous culture, ensuring holistic development and integration into the national mainstream.

The Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) is an India-made digital repository of TK available in several countries’ patent offices, including in the United States, Europe, Japan, and Russia. The TKDL has stopped 324 patent applications abroad based on the ‘prior art evidence’ availanle in the TKDL database with minimal costs. One of the significant challenges to indigenous rights and traditional knowledge creation was the COVID-19 pandemic. India came up with several measures to empower artists through online transitions as well as safeguards against piracy. Additionally, India supported MSMEs and vulnerable groups whose right to expression was severely affected by the pandemic. India’s NITI Aayog National AI Strategy emphasises the roadmap to AI integration in crucial sectors like health, agriculture, and education, making cultural diversity in datasets essential. Additionally, India’s AI Governance Guidelines empower the communities in the Global South by focusing on community consent and data provenance. India is uniquely placed to lead the TK Repository initiative.

India is playing a key role in the Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (IGC). IGC-WIPO seeks to protect indigenous medicinal knowledge, community-held healing practices, art forms, music, folklore, tribal designs, patterns, plant varieties, and biological materials connected to culture.

Conclusion

India’s proposal to establish a Global Traditional Knowledge Repository is the need of the hour to develop pluralistic norms rooted in community consent, institutional cooperation, and protection of indigenous knowledge systems. The repository can help to prevent biopiracy, misappropriation, and data colonisation presently affecting countries of the Global South countries. As AI rapidly reshapes innovation in crucial sectors like agriculture and health, digital economies need to co-design the global IP governance. India’s commitment to speak as the Voice of the Global South continues to empower the least protected communities in the world.

Add comment