|

Listen to article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

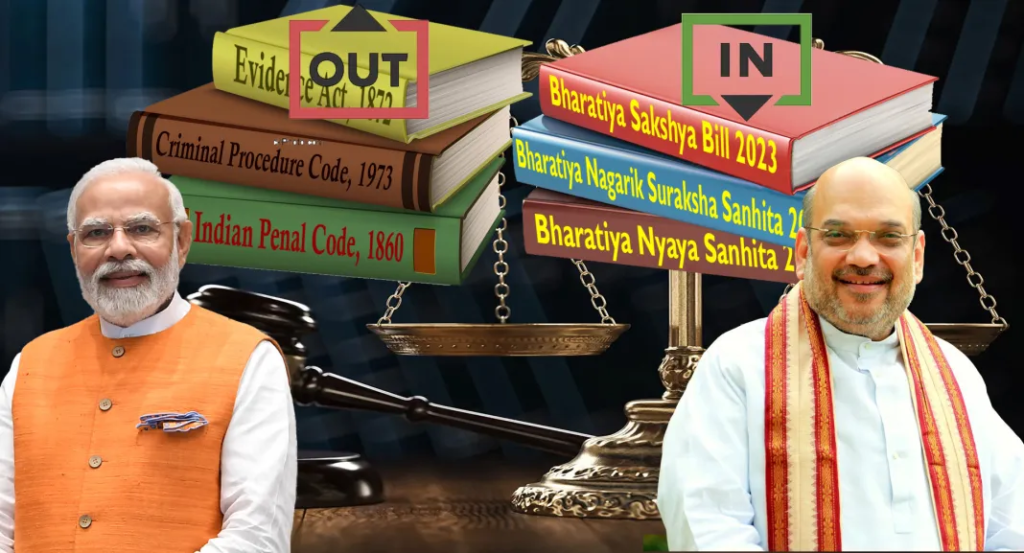

On 11 August 2023, Home Minister Shri Amit Shah brought 3 new Bills viz. Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Bill, 2023, the Bhartiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita Bill, 2023 and the Bharatiya Sakshya Bill, 2023 by repealing Indian Penal Code, 1860, Criminal Procedure Code, (1898), 1973 and Indian Evidence Act, 1872, which were enacted by the British and passed by the British Parliament.

The evolution of law and more specifically criminal law has a long and evolutionary genesis. Early Indian thought and tradition about rule and law has never been based on legality or deliberation of individuals in societies, as in the case of western tradition, but on moral principle and authority and is considered of divine origin. The classical law of India is characterized not by positive law and legality but by moral authority and duty that is called Dharma. Dharma refers to the totality of duties which is incumbent on individuals and the eternal rules which maintain the world. Anarchy or Arajakata is the outcome of the absence of dharma. The Supreme Court of India’s logo is ‘Yato Dharma Tato Jaya’. The onset of anarchy or Arajakata was caused by deviation of people from the path of dharma, righteous conduct. Anarchy is ‘when the weak are oppressed and exploited at the hands of the strong.’ Arajakata refers to the condition when matsyanyaya or the law of the fish prevail when the strong swallow the weak without either any guilt of conscience or societal punishment. Both order and anarchy are thought of normatively in classical Indian tradition, more particularly in the traditions of reflections and practice initiated by the Vedas and the Upanishads. Arajakata is caused by greed and ‘the tendency ingrained in every individual to acquire for himself as much of worldly goods as possible to the detriment of others.’

The rules of social order were codified by the ancient seers, in the rationalistic age, in treatises which are known as the Dharmasutras. The Dharmasutras were composed in abstruse style and so were not intelligible to the populus. The smrtis or the Dharmasastras are the compendia, systematically epitomising the material contained in the grhya and Dharmasutras. The smrtis, like any other text, are the great reflectors of the life of the people of their period. Among the eighteen smrtis, Manusmrti stands foremost among the principal work of its class, which acts as the source of Indian law for centuries. Tradition ascribed the primary authorship of the Manusmrti to sage Manu, whose name occurs right from the Vedas down to pre-smrti literature. The Manusmrti, itself refers to Bhrigu as the second author. Manusmrti preserves the traditions, precepts, customs and rules of conduct and rites in the Vedas.

After Manusmrti, it is the ancient Indian character Chanakya, whose work Arthashastra, a draft of a constitution for an ideal state, remained a source of law for India for long. Chanakya played a lead role in setting up administrative machinery, policy planning and in making laws, rules, and regulations of the state departments.

Muslim invasion of India paved the way for Mohammedan law. The Mohammedan criminal law was defective in many respects. It gave no weight to the testimony of unbelievers. Under Mughal rule, civil justice and revenue laws came under the authority known as Diwany whereas military and criminal justice came under Nizamat. Before Robert Clive established the suzerainty of the East India Company, the native system was as follows: – there was a Nazim, a supreme magistrate invested with the power to try capital offenders. Just below him was a Deputy Nazim, then a Foujdar, then a Cotwal and outside the capital in the mofussil districts the Zamindars (landowners).

The Britishers did not establish the legal system in India overnight. Warren Hastings was the first Englishman who persuaded the Hindu Pandits of Benares to unlock the treasures of Sanskrit literature, and to aid him in codifying the Hindu laws. Hastings personally attended courts of Muslim rulers of Bengal and refused to buy the British prejudice that India was ruled by despots. Hastings concluded that ‘Indian knowledge and experience as embodied in the varied textual traditions of Hindus and Muslims were relevant for developing British administrative institutions.’ He encouraged a group of younger servants of the East India Company to ‘study the ‘classical’ language of India — Sanskrit ‘as part of a scholarly and pragmatic project aimed at creating a body of knowledge that could be utilised in the effective control of Indian society.’

In 1769 European Supervisors were appointed. In 1772 new courts were set up. In each district there was a Foujdar Adalat or criminal court composed of Mohammadan officers. In each there was a Kazi, a mufti and two maulvis who tried all criminal cases in the presence of a collector, whose duty was to see that the trial was fairly concluded. These courts were altogether found inefficient and in 1781, English Judges of civil courts were invested with criminal jurisdiction as well. But this too did not work well and in 1793 Lord Cornwallis passed Judicial Regulations which formed the foundation of the existing system. Bombay was the first province in India in which a penal code was enacted. It was Mount-Stuart Elphinstone, the then Governor of Bombay who issued a simple and brief penal code in 1827 which remained in force till it was superseded by the Indian Penal Code. In 1833, the British united the whole of India under one administration and started codifying law for all India.

However, it was only after the arrival of Lord Macaulay in India that the Indian Penal Code received the highest attention and was codified. A commission was appointed consisting of Lord T.B. Macaulay, J.M. Macleod, G.W. Anderson and F. Millett. While submitting the report the commission wrote to the Governor General of India in Council that, ‘The Penal Code which, according to the orders of Government of the 15th June 1835, we had the honour to lay before your Lordship in Council on the 2nd of May last, has now been printed under our superintendence, and has, as well as the Notes, been carefully revised and corrected by us, while in the Press’. The commission settled the draft of what long afterwards became the Indian Penal Code. On the long time consumed by the commission Lord Macaulay’s team wrote, ‘The time which has been employed in framing this body of law will not be thought long by any person who is acquainted with the nature of the labour which such works require, and with the history of other works of the same kind’. The difficulties encountered by the team were visible.

The report says, ‘It is hardly necessary for us to intreat your Lordship in Council to examine with candour the work which we now submit to you. To the ignorant and inexperienced the task in which we have been engaged may appear easy and simple. But the members of the Indian Government are doubtless well aware that it is among the most difficult tasks in which the human mind can be employed; that persons placed in circumstances far more favourable than ours have attempted it with very doubtful success; that the best Codes extant, if malignantly criticised, will be found to furnish matter for censure in every page; that the most copious and precise of human languages furnish but a very imperfect machinery to the legislator; that, in a work so extensive and complicated as that on which we have been employed, there will inevitably be, in spite of the most anxious care, some omissions and some inconsistencies; and that we have done as much as could reasonably be expected from us if we have furnished the Government with that which may, be suggestions from experienced and judicious persons, be improved into a good Code’.

The Indian Penal Code draft of Macaulay and team underwent a very careful revision at the hands of Sir Barnes Peacock, Chief Justice, and puisne Judges of the Calcutta Supreme Court. On 26th April 1845, The Governor-General in Council instructed that, ‘Some step should be taken towards a revision of the Code with a view to its adoption, with such amendments as may be found necessary, or to its final disposal otherwise.’ The report of the Indian Law Commissioners submitted to the Honourable the President of the Council of India, in Council, dated 23rd July 1846. The report comprises two volumes.

Sir Barnes Peacock in his letter dated 23rd July 1846 said, ‘We have with great pains and care examined, compared and digested, the voluminous papers containing commentaries and strictures on the Penal Code transmitted to us with Mr. Bushby’s letter, and having reviewed the Code generally with reference thereto, we have directed our more particular attention to the chapters of the greatest importance.’

The Indian Penal Code draft originally drafted by Lord Macaulay’s team was improved further in 1846 and remained in that shape for no less than twenty-three years (Macaulay’s team submitted the report in 1837). This was due to the various prevailing factors including the Great Indian Mutiny and the transfer of the Government from the company to the Crown. The decadal delay in applying the IPC ended when the Penal Code was finally passed into law as Act XLV of 1860 and was followed a year afterwards by Act XXV of 1861, the first Code of Criminal Procedure. The Indian Penal Code was brought into force from the 1st of January 1862.

In February 2011, Lord Anthony Lester of Herne Hill QC (UK), in his keynote address on ‘Multiculturalism and Free Speech” at the Commonwealth Law Conference in Hyderabad said that, ‘the IPC embodied some relics of English medieval ecclesiastical law and of the Court of the Star Chamber and it was high time India changed its penal code’. Attempts were made to amend the Indian Penal Code and the Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Bill, 1972, introduced in the Rajya Sabha on 11 December 1972 was vital amongst all. However, as the House of the People was dissolved in 1979, the Bill, though passed by the Council of States, lapsed. In 1995, pursuant to the reference made by the Government of India, the Law Commission undertook a comprehensive revision of the Indian Penal Code, with special reference to the Indian Penal Code (Amendment) Bill, 1978, in the light of the changed socio-legal scenario. On 12 August 2010, the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Bill, 2010, which was introduced on 22 March 2010 in the Lok Sabha was passed by the parliament. But overall, there has not been any great change regarding the basic principles underlying this great and essential branch of law envisioned and codified by Lord Macaulay and his team.

If the three laws, as introduced in Lok Sabha are passed, the soul of the three new laws will be to protect all the rights given to Indian citizens by the constitution, and, their purpose will not be to punish as the British intended but to give justice. These three laws made according to an Indian thought process will bring a huge change in our criminal justice system.

Add comment