|

Listen to article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

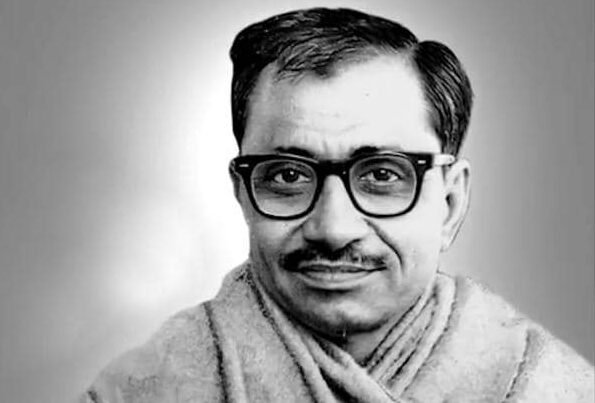

The concept of Antyodaya stands for identifying the last person in the socio-economic pyramid for the purpose of inclusive growth and sustainable development. Indian political thinker Deendayal Upadhyaya (25 September 1916 – 11 February 1968), President, the Bharatiya Jana Sangha, put it forward as an organic and integral approach to social inclusion in the mid-1960s, emphasizing on economic and political aspects of relative poverty. Since his views on addressing poverty are mainly based on decentralized ‘swadeshi’ economy and egalitarian politics, Deendayal conceptualised a three-pronged scheme with respect to a holistic effort towards poverty eradication: ‘Antyodaya’ (the rise of the last person in the queue), ‘Har haath ko kaam, har khet ko paani’ (work for every hand, water for every field) and ‘Charaiveti, charaiveti’ (move on, move on). His reflection on how to rescue the nation of extreme poverty lies in his indigenous worldview: “We want neither capitalism nor socialism. We aim at the progress and happiness of ‘Man’, the Integral Man.”

The idea of Integral Man is rooted in the conceptualisation of a person who carves out a true sense of personality and remains authentic in his aspirations. Accordingly, an economic system suited to the requirements of such concepts must be constituted with the objective of securing the minimum needs of the people on one hand, and safeguarding the integrity of the nation, on the other. Deendayal aptly says: “With the support of universal knowledge and our heritage, we shall create a Bharata which will excel all its past glories, and will enable every citizen in its fold to steadily progress in the development of his manifold latent possibilities and to achieve through a sense of unity with the entire creation, a state even higher than that of a complete human being; to become Narayana from ‘Nara’.”

The organic notion of Integral Humanism regards Dharma as the guiding principle of the state. Drawing distinction from religion, Dharma is the moral compass of government and the society. Deendayal, therefore, rejects the doctrine of ‘statism’ and espouses liberal notions about the liberty of the individual within the parameters of social responsibility. His idea of the State has a secular character with the co-existence of a unitary constitutional structure and decentralized operation of power. He speaks for building a safety net into our policies for the underprivileged or the disabled while simultaneously rewarding the meritorious or gifted, in order to foreclose the usual clash between the politically empowered poor majority and the economically empowered rich minority in a democratic system. In such an inclusive scheme, each and every person, especially the least advantageous one, who appears as Daridra Narayana in Swami Vivekananda’s description, receives systemic attention for development.

The rationale behind any economic system is its ability to provide the minimum basic necessities of human life such as food, cloth and shelter to everyone. The inevitability of work guarantee is recognised in a self-reliant production process while a contrary system that obstructs the production activity of the people is self-destructive. Deendayal, therefore, argues that our economic objectives must include assurance of minimum standard of living to every individual and meaningful employment provisions to every able-bodied citizen. Thus, he says, “The guarantee of work to every able-bodied member of the society should be the aim of our economic system.” Deendayal’s insistence on full employment is based on the convictions that a productive use of manpower is required for economic prosperity and for ensuring respectful contributions of workers to society.

In his economic vision, Deendayal confers prominence to seven Ms: man, material, money, management, motive power, market and machine. As the foundational components of a sound production system for a country, he argues that these seven elements constitute the comprehensive framework of an economy enabling it to serve people’s needs in a self-reliant manner. Given the fact that India is sufficiently endowed with all of the seven elements, the country’s economic system has the ability to meet the basic requirements of all its citizens without causing any harm or dislocation to human ecology. Swadeshi and decentralisation approaches lie at the core of Deendayal’s economic system. He says, “Man, the highest creation of God, is losing his own identity. We must re-establish him in his rightful position, being him the realization of his greatness, reawaken his abilities and encourage him to exert for attaining divine heights of his latest personality. This is possible only through a decentralized economy.”

The notion of Antyodaya consequently remains a key component of ‘Integral Humanism’, a philosophy that advocates the simultaneous and integrated programming of the body, mind, intellect and soul of each and every human being. Thus, Deendayal’s ideational contribution is a synthesis of the spiritual and the material, and the individual and the collective in the economic and political life. Visualizing a decentralized polity and a self-reliant economy with the village as the base for India, he reiterates the need for a perfect harmony between individuals and society: “To mould nature (prakriti) to achieve social goals is culture (samskriti), but when this nature leads to social conflict, it is perversion (vikrití).”

In essence, the yardstick for measuring economic plan and progress is not the person situated at the highest level of society rising above on the economic ladder, but the one who is located at the lowest level. Notably, the Indian government is currently engaged in profound execution of this Antyodaya concept, offering an actionable model of community development based on self-reliance. Evidently, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said, “Inspired by Pt. Deendayal Upadhyaya, 21st century India is working for Antyodaya. Our government is working to reach the last person in the society, to bring the benefits of development to them.” Recognising poverty as a systemic crisis, the idea and practice of antyodaya become helpful in scholarly and policy making domains for identifying and addressing the issue in a holistic and sustainable manner.

Add comment