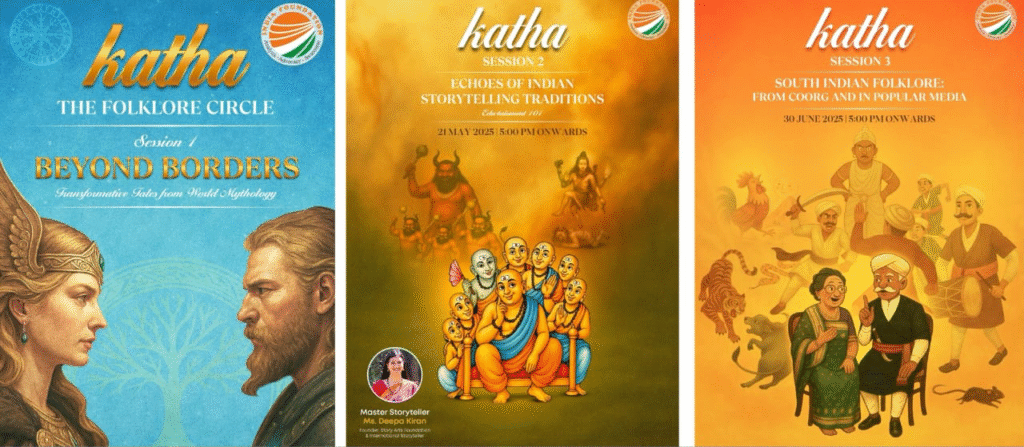

When Katha Session 4, “Viking Sagas with a Hint of Masala” was just around the corner on 24 July 2025, I thought of the vibrant and thought-provoking experience provided by Session 3. Titled “South Indian Folklore: From Coorg and in Popular Media”, the evening function beautifully showcased how stories can cross borders, connect cultures, and stir something deep within our collective memory.

Kushalappa’s Stories from Dakshin

The evening opened with author Nitin Kushalappa narrating the first two stories from his much-loved book Dakshin: South Indian Myths and Fables Retold. Though the book is intended for younger readers, the stories he chose to share carried lessons that spoke to everyone in the room, regardless of age.

The first story, The Persistent Myna, follows a small bird who faces one obstacle after another but refuses to give up. Even when others mock her or doubt her, she stays focused and keeps trying. In the end, her persistence pays off. It’s a gentle but powerful reminder that resilience, optimism, and quiet determination can lead us further than brute strength ever could.

The second story, Bala Nagamma and the Evil Sorcerer, tells of a young woman who is abducted by a dark and powerful sorcerer. Instead of succumbing to despair, she uses her wit and inner strength to outsmart her captor and regain her freedom. The tale celebrates courage, cleverness, and feminine strength, values deeply woven into the fabric of India’s storytelling traditions.

Through these simple yet profound narratives, Nitin did much more than just tell stories. He brought to life the oral traditions of Kodagu (Coorg), breathing fresh relevance into age-old wisdom. In doing so, he reminded us that folklore is not just about preserving the past, it’s about carrying forward a moral compass rooted in our civilisational ethos.

Orson Passi’s Retelling of Persephone

Bringing in a cross-cultural dimension, Mr. Orson Passi, Second Secretary (Political) at the Australian High Commission, shared a retelling of the well-known Greek myth of Persephone. In this story, Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, is suddenly taken away by Hades, the god of the underworld. Demeter’s grief over her daughter’s disappearance causes the world to fall into barrenness and sorrow. Eventually, a divine agreement is reached, Persephone would spend part of the year in the underworld with Hades and the rest with her mother on Earth. This movement between worlds restores balance to nature and gives rise to the changing seasons.

But Orson’s telling went beyond mythology. He drew out the deeper symbolism within the tale, the rhythms of loss and return, the longing between separation and reunion, and the idea of renewal that comes after a period of stillness or suffering. These are themes that echo strongly within the Indic tradition too, where stories often reflect the cyclical nature of time, the transitions between light and shadow, and the harmony between life and death.

Hearing this myth in a space otherwise filled with stories from the hills of Coorg created a striking moment of connection. It reminded us that, no matter where we come from, cultures across the world reach for the same truths. Whether through a Greek goddess or a Coorgi fable, human storytelling often circles back to the same eternal questions, and in doing so, it shows us just how closely we are all bound.

Myth, Folklore, Folktale, Legend

One of the enriching parts of the session was a short but meaningful discussion on the different kinds of stories we often encounter, and how to distinguish between them. These terms are often used interchangeably, but each carries its own weight and role in shaping how we understand a culture’s worldview.

A myth, for instance, is more than just an old tale. It is a sacred narrative that speaks of gods, creation, and the cosmic order, stories that try to explain the mysteries of existence and the forces that govern the universe.

Folklore is broader. It includes not just stories, but a community’s entire cultural expression, customs, rituals, songs, sayings, and beliefs, passed down through generations as a way of life.

A folktale, by contrast, is usually a secular story told for entertainment or moral instruction. These are the kinds of tales grandparents pass on to children, stories filled with animals, tricksters, ordinary heroes and heroines, often with a strong ethical message.

And then there are legends, stories that may have a historical root, grounded in real people or events, but which evolve in time into larger-than-life narratives. These are often how communities preserve their heroes, their trials, and their victories, even if the details are embroidered upon the basic weft of the plot

Understanding these distinctions added a new layer to how we experienced the session. Bala Nagamma stepped into view not just as a character, but as a classic figure of Indian folklore, the everyday heroine who triumphs through cleverness. Persephone, in turn, stood clearly in the realm of myth, an archetype of divine feminine power navigating cycles of loss, darkness, and return. By recognising the form each story takes, we began to see how different cultures have built their moral and metaphysical foundations through narrative.

Why Katha-3 Was Special and Why Katha-4 Will Be No Less

Katha-3 was a gentle but powerful reminder that stories are not just cultural artifacts, they are the living signatures of a civilisation. They hold memory in their folds, pass wisdom across generations, and offer a bridge between the personal and the philosophical. Whether born in the misty hills of Coorg or the mythical fields of ancient Greece, each story shared that evening carried a timeless truth, about human nature, cosmic rhythm, and the moral imagination that binds us all.

If Katha continues in this spirit of thoughtful storytelling and shared reflection, it will not just inform or entertain, but continue to nourish both the intellect and the soul.

Add comment