Orientalism, as conceptualised by the renowned scholar Edward Said in his seminal work “Orientalism” (1978), refers to the Western academic and intellectual tradition of representing and interpreting the East, particularly the Middle East and Asia. While Said’s primary focus was on the Arab world, the principles of Orientalism extend to various regions, including the Indian subcontinent. This essay explores the intricate connection between Orientalism, colonialism, and its impact on Indian historiography. It examines how the West’s constructed narratives have shaped perceptions and influenced the study of Indian history.

Orientalism as an Intellectual Armature of Colonialism

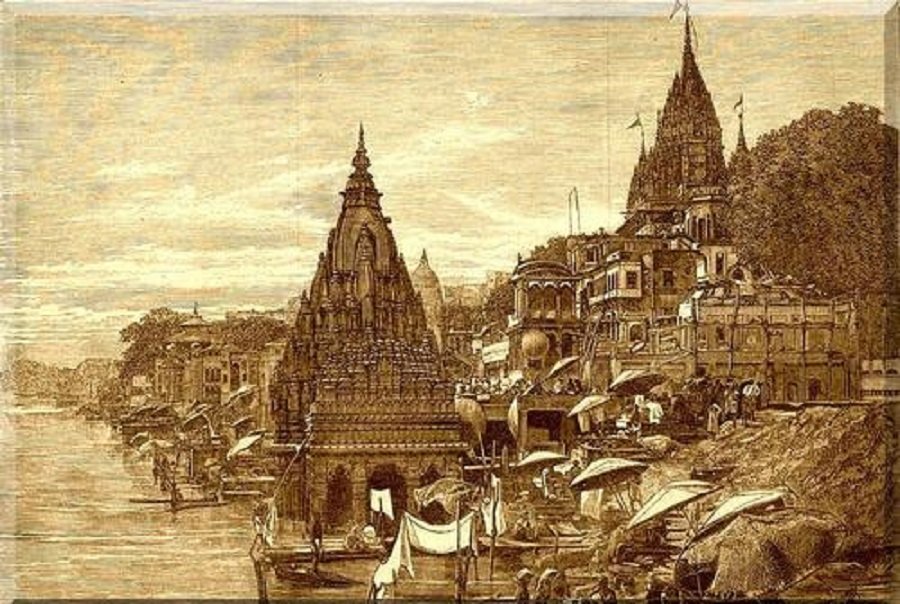

Orientalism, in its historical context, played a pivotal role in justifying and perpetuating European colonialism. European powers, during the age of imperialism, sought to establish dominion over various parts of Asia, including India. Orientalist scholars, often aligned with colonial enterprises, provided the intellectual foundation for this domination by constructing narratives that reinforced the theory of Western superiority on Eastern polities and cultures. The Orientalist gaze tended to essentialize and exoticize the cultures of the East, depicting them as static, mysterious, and backward. This constructed image served colonial powers by providing a rationale for their intervention in the affairs of colonised nations. The assumption of Western cultural and intellectual superiority not only justified colonisation but also facilitated the imposition of European norms and values onto indigenous societies. Orientalism, therefore, functioned as an intellectual armature, providing the ideological ammunition for colonial endeavors. The knowledge produced by Orientalist scholars became a tool for control and domination, shaping policies and attitudes toward the colonised regions.

Textual Fetish in Indian Historiography:

The impact of Orientalism on Indian historiography is palpable, as the narratives produced by Western scholars influenced how Indian history was perceived and recorded. The colonial encounter led to the creation of an “Oriental knowledge” shaped by Western perspectives, biases, and interests. One aspect of this influence was the fetishisation of Indian texts and traditions. Western scholars often approached Indian history through a selective and romanticised lens, highlighting aspects that fitted their preconceived notions of the exotic and mystical East. Ancient Indian texts, such as the Vedas and the Upanishads, were interpreted in a manner that reinforced Orientalist stereotypes. This textual fetish not only distorted the understanding of Indian history but also marginalized indigenous voices and perspectives. Native interpretations of history were often dismissed or overwritten by Western narratives that portrayed the colonised people as passive subjects, lacking agency and intellectual capabilities.

Impact on Indian Identity and Self-Perception:

The Orientalist reconstruction of Indian history had profound implications for the identity and self-perception of the colonised population. As Western narratives permeated academic discourse, they influenced how Indians saw themselves and their history. The imposition of an alien narrative created a sense of cultural inferiority and a distorted understanding of one’s heritage. The internalisation of Orientalist perspectives led to a dissociation from indigenous knowledge systems and traditions. It became essential for Indians, especially in elite circles, to conform to Western norms and values if they wanted to be considered progressive or enlightened. This cultural hegemony, perpetuated through Orientalist historiography, had lasting effects on post-colonial India’s struggle for self-definition and identity. The legacy of Orientalism continues to pose challenges in contemporary Indian historiography. The process of decolonisation did not automatically eradicate the deeply ingrained Orientalist biases in historical studies. Even today, scholars grapple with the task of untangling the web of distorted narratives and recovering the authentic voices and perspectives of the Indian people. Efforts have been made to decolonise the historical discourse by incorporating diverse perspectives, challenging Eurocentric interpretations, and acknowledging the agency of indigenous actors. However, the imprint of Orientalism is resilient, and its influence lingers in academic structures, methodologies, and institutional frameworks.

Conclusion

Orientalism’s role as an intellectual armature of colonialism and a textual fetish in Indian historiography underscores the intricate connection between knowledge production and power dynamics. The West’s construction of narratives about the East served not only to justify colonial domination but also to shape the very identity and self-perception of the colonised. The impact of Orientalism on Indian historiography endures as a challenge for scholars seeking to decolonise the narrative and present a more authentic, inclusive, and nuanced understanding of India’s rich and diverse history.

Add comment