|

Listen to article

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The history of Christianity in India is complex, marked by phases of missionary zeal aimed at spreading the faith among the Indian populace, as well as periods of adaptation and integration where Indian Christians sought to meld their religious identity with their indigenous cultural roots. During the colonial era under British rule, this tug-of-war between Christianisation – the attempts by missionaries to convert Indians and reshape Indian society through a Western Christian lens – and Indianisation – the efforts of Indian Christians to syncretise their faith with Indian philosophical and cultural traditions – played out in profound ways. This study will analyze the transition from the predominant early colonial model of aggressive Christianisation driven by missionary activities to an increasingly popular mid-to-late movement towards Indianising Christianity to make it more authentic and indigenous to the Indian context. Critical factors like the role of British colonial policy, the reactions of Hindu revivalists, the rise of Indian nationalism, and the efforts of critical Indian Christian thinkers and reformers will be examined. Ultimately, it will be shown how Indian Christianity was transformed from a “foreign implant” to a religion increasingly rooted in Indian philosophical traditions and cultural practices by the early 20th century.

Early Phase: Christianisation Under Colonial Rule

When the British East India Company began its colonial occupation of India in the early 1600s, it brought an evangelical zeal to spread Protestant Christianity in its newly acquired territories. Though prohibitions initially existed on interfering with native religious practices, by 1813, the path was cleared for an influx of missionary activities aimed at Christianising the Indian population. Groups like the Anglican Church Missionary Society, Baptist Missionaries, and other evangelicals undertook sprawling efforts to convert Indians through preaching, tract distribution, school building, and publishing vernacular translations of the Bible and religious texts. These conversion efforts were predicated on an attitude of spiritual and cultural superiority – the belief that Christianity represented the culmination of God’s revelation to man and that Indian religious traditions like Hinduism were heathen superstitions that needed to be extirpated and replaced wholesale by Christian doctrine. As the missionary leader William Carey declared, the mission was “not to accommodate Christianity to the long-winded idolatries and puerile superstitions of Asia” but rather to facilitate their “entire abolition.” From this standpoint, Hinduism, in particular, was treated with utter intolerance, decried as idolatrous paganism that degraded women and promoted horrific practices like sati.

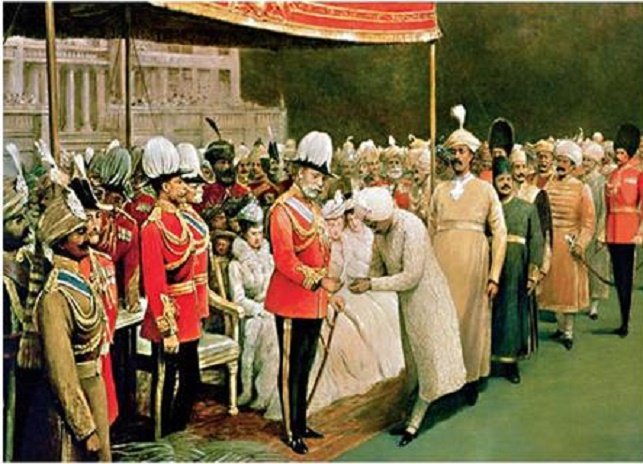

The policies and worldview of the British colonial authorities facilitated this aggressive Christianising project. Though religious tolerance existed to a degree, Christians were given preferential treatment and had the implicit sanction of the colonial state behind their proselytizing activities. Nehru later criticized “the policy of the East India Company and the early British administrators in creating a kind of moral bases for the propagation of the Christian religion in India.” In the early to mid-1800s, examples abounded of the coercive measures and power imbalances inherent in the Christianisation effort. Hindu pundits were subjected to demeaning disputations and public shaming by missionaries. Orphans and children from low-income families were systematically inducted into mission boarding schools to receive a Christian education and be shielded from their “idolatrous” native upbringing. Dalits were explicitly targeted for conversion based on the myth that they were descendants of Indian Jews who had tragically regressed into paganism. Laws were passed in the 1840s, allowing Hindus to convert to Christianity while prohibiting the reverse course. Lord William Bentinck’s abolition of sati and other reforms were colored by distinctly Christian cultural imperialist attitudes, which sought to “civilize” and remake Indian society along Western models. This asymmetric power relationship skewed heavily in favor of Christianity – and this ultimately helped sow the seeds for reactionary Hindu revivalism and rising nationalism in India.

Rise of Hindu Revivalism & Resistance

The unabashed project of transforming Indian society through Christianisation provoked a fiery backlash from Hindu revivalist groups who arose to combat missionary excesses and British cultural imperialism. Organizations like the Brahmo Samaj, Arya Samaj, and the Hindu Mahasabha emerged in the 19th and early 20th centuries as vocal opponents of conversions. They became champions of social reform within native Indian cultural and religious frameworks. Hindu revivalist leaders like Swami Vivekananda, Swami Dayananda, and Aurobindo Ghose sought to counter Christian preaching by reasserting Hindu philosophical thought and aiming at what were seen as distortions of Indian spirituality propagated by missionaries. Vivekananda’s “Raja Yoga” and Aurobindo’s “Essays on the Gita” touted the universality and continued relevance of Hindu scripture and Vedanta philosophy while dismissing the need for Christian exclusivism. Dayananda’s Arya Samaj, in particular, was militantly opposed to the onslaught of Christian proselytizing, preaching a neo-Vedic doctrine and refuting claims of Hindu superstition. These revivalist movements also worked towards societal reform through renewed interpretations of Hindu texts rather than rejecting Indian culture wholesale as missionaries did.

Notably, Hindu revivalists attacked the moral and intellectual basis on which Christianity sought to undermine and supplant Indian civilization. Where British authorities claimed Indian religious traditions subjugated women, revivalists cited examples of female education and gender egalitarianism in Vedic society. Against accusations of idolatry, philosophies like Advaita Vedanta were invoked to explain Hindu metaphysics as essentially monotheistic and non-idolatrous. Rather than backward superstition, Hindu leaders now championed their dharmic traditions as embodying profound philosophical insight and social wisdom humanity had lost track of. This strengthening Hindu resistance was occurring in tandem with the rising tide of Indian nationalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Bal Gangadhar Tilak syncretically blended Hindu revivalism with emerging anti-colonial nationalism, galvanising widespread civil obedience against British rule. Christianity became increasingly seen as the “provincial badge of racial and cultural deracination,” according to scholar M.M. Thomas. By vehemently defending indigenous spirituality and confronting ideological attacks against Hinduism, the revivalists fostered nationalist rejection of Western cultural hegemony and the colonial civilizing mission. In this shifting socio-political landscape, some prominent Indian Christians were compelled to defend their faith and reconcile it more wholesomely with Indian heritage. There arose the conviction that an indigenized, Indianised Christianity was needed to replace the imposed and alien implant of the colonial missionary enterprise.

The Indianisation of Christianity

From the mid-19th century onward, pioneering Indian thinkers sought to present Christianity as compatible with, and even complementary to, Indian spiritual traditions rather than positing it as a rival, foreign implant. By translating Christian theological concepts into indigenous philosophical frameworks, reinterpreting the Bible through Indian philosophical lenses, and recuperating Christianity as a reform movement rooted in Indic antecedents, these figures endeavoured to make Christianity a more authentically Indian religion in thought and practice. Central to this movement of Indianising Christian thought was the conviction that beneath seeming differences between Hindu and Christian doctrine existed common transcendent truths about the nature of God, morality, and spiritual liberation. Influential Indian Christian thinkers were able to draw structural and conceptual parallels between tenets like the Hindu idea of non-dual Brahman and the Christian conception of the Holy Trinity as “sat-cit-ananda” (being-consciousness-bliss) or between Hindu Advaita philosophies of non-dualism and Christian theoretical frameworks of absolute divine unity. Most audaciously, some even traced cultural threads connecting Christ’s teachings and early Christianity’s gnostic currents to ancient Upanishadic insight and Vedantic thought.

For example, Brahmabandhav Upadhyay, a Hindu convert to Catholicism, made concerted efforts to couch Jesus Christ as the ” Christ of Eternal Religion” in his numerous writings in the 1890s and early 1900s. Drawing on Upanishadic texts, Rammohun Roy, and neo-Vedanta philosophy, Upadhyay argued that Christ was the redeemer tradition foretold in Hindu scriptures – one heralding the supreme being of the “Eternal Religion” (Santana Dharma) that was the basis for Hinduism, Christianity, and all authentic faiths. He refuted missionary dismissals of Hinduism as idolatrous, reinterpreting Hindu worship through non-dual Advaitic frameworks. “It is from not a proper understanding of our thoughts and words that they [missionaries] have misconstrued us to idolaters,” Upadhyay wrote. His attempts were built on the foundations of earlier Indian Christians like Brahmabandhav Ram Mohan Roy and Krishna Mohan Banerjee. These forerunners had already incorporated Hindu metaphysical concepts like Maya, moksha, and avatar into their Christian thought and polemics against European missionaries’ critiques of Hinduism. Banerjee, regarded as the first great Indian Christian theologian, even audaciously reclaimed the “Hindu Catholic” label – seeing his faith as a unitive fulfillment and extension of Hinduism’s highest philosophical insights. For thinkers like them, the incarnation of Christ represented, according to Robert Eric Frykenberg, “the ultimate avatar” that united diverse world religions in a joint universality.

Sadhu Sundar Singh, V. Chakkarai, and P. Chenchiah would continue building on this reconceptualisation of Christian doctrine through the lens of Indian philosophies like Advaita Vedanta and writings like the Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita, and yogic thought. By boldly integrating Hindu and Christian, they thought, these Indian Christian reformers hoped to transcend the divisive colonial division of east vs. west, foreign vs. native – and restore what they felt was an ancient spiritual unity underlying the world’s religions. This intellectual indigenisation effort was accompanied by a parallel endeavor to imbue Indian Christianity with culturally authentic ritual practices and forms of worship. Thinkers like Brahmabandhavs P. Brahmabandhuva Upadyaya and A. Chakkarai criticized the stark disconnection in Indian churches between Western modes of prayer and India’s devotional traditions like bhakti poetry, iconography, ash markings, and ceremonial rituals. Indian Christians should be able to pray, sing hymns, meditate, and worship through native idioms, practices, and symbols they innately understood – not replicate soulless Western European methods of ceremonial rigidity, they argued.

Some Hindu practices like having arati lamp ceremonies, keeping murti icons in churches, using bindi tilaks, worshipping through Carnatic-style devotional group singing, and adopting Indian styles of asceticism were gradually accepted into Indian Christian churches as indigenous devotional forms. New ashram movements led by Christians with adopted Hindu monastic lifestyles and modes of guru-shisya relations arose, integrating ancient Indian spirituality and modern Christianity. These ritual forms reconnected Christianity to the immortal heart of Indian religious piety and mysticism. Often led by former Hindus like Brahmabandav Upadhyaya or Sadhu Sundar Singh, the movements represented interfaith re-integration of Christ’s teachings with Indian spiritual roots and seekers’ heartfelt experience.

Varying impulses drove the Indianisation of Christianity – apologetic efforts to salvage Hinduism and show Christianity’s universality, postcolonial resistance to Western religious exclusivism, developing theories of religious pluralism, and a deep spiritual yearning to reclaim native Indian forms of devotion for Christianity. These many currents and motivations culminated in the process whereby Christianity came to be “clothed in an Indian form,” according to M. M. Thomas. What was once a foreign imposition of colonial Western missionarism becoming re-rooted in ancient Indian wisdom and more accessible – even naturally expressed through – Indian cultural practices.

Conclusion

The story of Christianity’s complex evolution in India pivoted from an early period where missionaries sought complete Christianisation of the population – denigrating and demolishing indigenous Indian traditions while spreading what was essentially a foreign colonial religion by coercive means – towards an increasingly self-conscious movement of Indianising Christianity and recasting the religion through Indian spiritual and philosophical frameworks. This reversal was provoked by many sociocultural factors, ranging from the rise of Hindu revivalism and Indian nationalism, which resisted Western cultural hegemony, to intrinsic efforts by Indian Christian thinkers to de-provincialise their faith and establish its perennial universal roots in the subcontinent’s ancient tradition of spiritual seeking. The outcome was an Indianised, indigenised Christianity captured in the new ritual forms, intellectual reconceptualization of theology through Indic categories, and belief in a pre-established Prisca Theologia underlying all world religions that had been proclaimed by some leading Renaissance Humanists in Europe five centuries earlier.

By removing the trappings of Western cultural exclusivism and imperial overtones, Indian Christians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries took strides towards what scholar Robert Eric Frykenberg described as “the achievement of an Indian self-identity and consciousness” through their religion. Christianity transitioned from being an alien imposition of colonial rule and indoctrination to seeking harmony with the perennial truths and devotional forms intrinsic to India’s civilisational identity. No longer anathema to the national heritage, Christianity was presented as a reform movement within the sustained Indian tradition of spiritual quest – allowing it to put down ever-deeper Indian roots in the coming century.

Add comment