Our people often refer to the 184 kings of Tripura, it is quite an unusual feat in history, that a single “Manikya Dynasty” ruled a kingdom for so many centuries. It is also said that our land is one of the oldest known kingdoms. The fact that many of the queens of Tripura also played significant roles in the history of this state is often overlooked.

The Tripura coins were first issued during the reign of Ratna Fa, who later came to be known as Ratna Manikya. He ruled from 1464 to 1489 AD and brought in development and many reforms. The “Standard Catalog of World Coins” Volume I (1986 Edition) by Chester L. Krause and Clifford Mishler said, “The origins of the Kingdom are veiled in legend, but the first coins were struck during the reign of Ratna Manikya and copied the weight and fabric of the contemporary issues of the Sultans of Bengal. He also copied the lion design that had appeared on certain rare tangkas (coins) of Nasir-ud-uddin Mahmud Shah (1445AD). In other respects, the designs were purely Hindu, and the lion was retained on most of the later issues as a national emblem.” The book went on to add, “The coins of Tripura are unusual in that the majority have the name of the king with that of his queen, and is the only coinage in the world where this has been done consistently.”

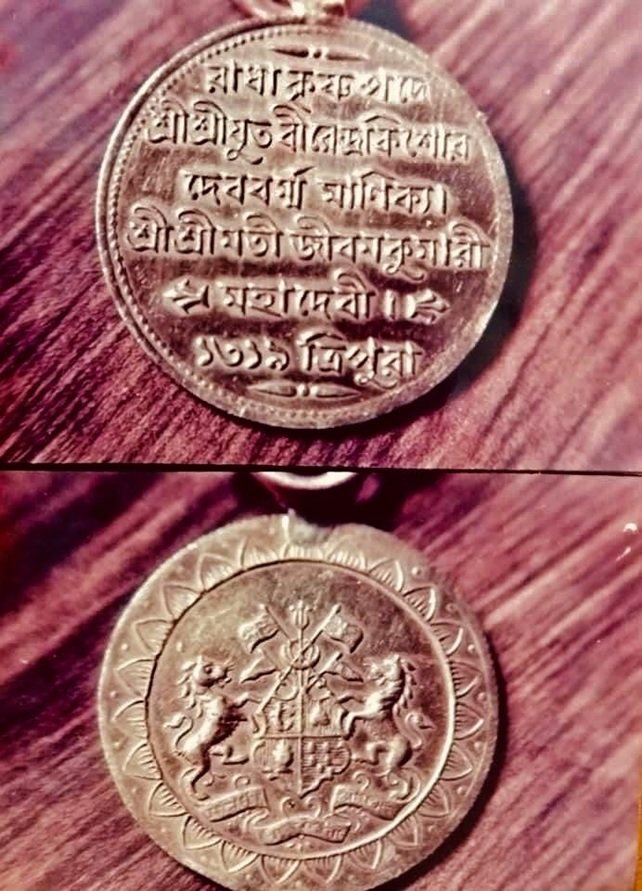

Later the Tripura coins became largely ceremonial but they were still found as the rulers did not want to surrender their right of coinage. I had seen a gold coin issued with the name of my maternal grandmother Maharani Jeevan Kumari Devi along with that of her husband Maharaja Birendra Kishore Manikya, which was dated 1319 Tripura Era (to get the Christian era one must add 590). On one side there was the Tripura insignia and on the other the name of the king and queen along with the date. I was told that it was customary for all maharanis to have a gold coin issued in their honour; it was referred to as a “sanad’ (royal proclamation). This perhaps was an indication that women enjoyed a status of recognition and respect throughout the history of this kingdom.

The custom called Chamari Kamani was once prevalent in the hills, where the prospective groom was required to work in the house of his future wife, to prove his worth. This custom is a reminder of the position that women in Tripura once held much unlike that of other parts of the mainland. The Chamari did all sorts of work, such as fetching water, firewood, cultivating the fields and any other task that was required in the household. He was watched over carefully by the girl’s family to ascertain his capabilities and diligence. They also observed his dealings with others, whether he was sincere and honest and also to ensure that he did not cross the “line”. If he did and was caught, he was packed off in disgrace. Sometimes he was ‘ragged’, by his future in-laws, who denied him proper meals and made him over –work. This ragging was done just to test his patience and tenacity.

An elderly man Ram Kumar (name changed), from the Reang Tribe, who was with us, recalled his experience of Chamari and how hard he was made to work. He also told me how he got nabbed red handed when he crossed “the line” with his fiancée and how he was almost rejected but was let off with severe punishment. He swore to himself, “Never again in that creaky bamboo hut !!”. When I asked him, “Why didn’t you quit and go home.?” He answered, “It was tough but every drop of sweat was worth it. It was love at first sight.” I could see the sadness in his eyes as he spoke, for he had just lost his wife.

The remarriage of widows led to a major hue and cry as late as the 19th century in the much-enlightened Bengal, which went on to influence and transform many cultural trends in Tripura. Social leaders like Raja Ram Mohun Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and many others raised their voices against the atrocities perpetrated on young widows by the Hindu society. Far from being able to remarry, they were either compelled to perform ‘sati’ (self-immolation) or live the life of an outcast.

It was these leaders who brought some relief to the widows. However, in the so called ‘primitive’ societies of Tripura, widow remarriage was quite popular since times unknown and was carried out with special ancient rituals, which were laid down for this kind of matrimony. Further, there was no social stigma attached to these marriages. The Ochai (priest) blessed the couple by striking a stone placed before the couple thrice with a takkal (chopper) and chanted “Let their lives be like the unending stream and their marriage as firm as this rock” After the ceremony there was much dancing and singing followed by a sumptuous feast, just like in any other normal wedding.

(To be continued..)

Enlighten Very Well