Introduction

Islands are valuable national assets. Situated along vital sea lanes and chokepoints, they support trade routes, provide military strategic advantages, and host economic activities such as tourism, fisheries, and other blue economy initiatives. However, they are delicate systems: forests, mangroves, and coral reefs represent ecological capital, and Indigenous communities have protection rights and unique cultures that must be respected and valued. Climate hazards, exemplified by the 2004 tsunami, impose clear limits. These realities demand careful management and development that comply with legal frameworks. The way forward involves balanced statecraft: establishing security and livelihood infrastructure, managing tourism and resources sustainably, adhering to the law at every stage, safeguarding Indigenous rights, and strengthening resilience against climate and seismic risks—ensuring that both strategic value and natural heritage are preserved sustainably together.

Islands as Security Enabler

Across the world, especially from the Western Pacific to the Indian Ocean, governments are prioritising and strengthening island infrastructure—ports, airstrips, fuel farms, and sensor networks—to deter coercion and keep commerce moving, while addressing environmental risks through impact assessments and targeted mitigation. The trend is clear: security and reliable strategic access are driving decisions.

- China has transformed Fiery Cross, Subi, and Mischief reefs into fortified air and naval bases—containing runways, missile shelters, and radars—despite ecological backlash. (Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative)

- Vietnam has fast-tracked land reclamation across all 21 Spratly features it controls to strengthen its presence and uphold its claims. (Reuters)

- The United States officially activated Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz on Guam following a thorough environmental review, emphasising the island’s continued significance as a Western Pacific hub. (pacific.navfac.navy.mil)

- Japan has deployed anti-ship and air missiles, along with littoral units, on islands such as Amami-Oshima, Miyako, and Ishigaki to fill gaps along the first island chain. Security is the priority, with local management of mitigations. (The Diplomat)

- Australia is extending and strengthening the Cocos (Keeling) Islands airfield—with a longer runway, improved lighting, drainage, and a new wharf—to support extended-range maritime surveillance. (Defence, Australian Parliament House)

- The Philippines and the US have extended access to island and forward sites (Balabac in Palawan; Cagayan and Isabela) for runways, fuel, etc. (U.S. Department of War and Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative)

- The UK and Mauritius have signed a treaty to secure the future of the US-UK base Diego Garcia (Chagos)—a strategic move to ensure long-term island basing in the central Indian Ocean. (GOV.UK)

- After independence, India positioned the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (ANI) as a strategic frontline outpost, developing ports, airfields, and naval infrastructure to deter threats and project influence across the Malacca approaches. In recent decades, the focus has expanded beyond defence to encompass economic opportunities—tourism, fisheries, and blue-economy projects—while the islands remain a powerful symbol of national sovereignty1.

What this means

- Countries do follow environmental rules on islands (impact studies, offsets, working only in certain seasons). But as far as security is concerned, strategy sets the schedule.

- So, they build the essentials first—runway, port, fuel, communications, sensors to protect the area and respond quickly.

- Then they implement safeguards and a monitoring system to support ecological and environmental protection, rather than halting the project.

- Governments regulate environmental impacts instead of allowing them to hinder essential access.

- Bottom line: Island security is the bedrock of national security. Protecting islands safeguards the nation.

Andaman and Nicobar Islands

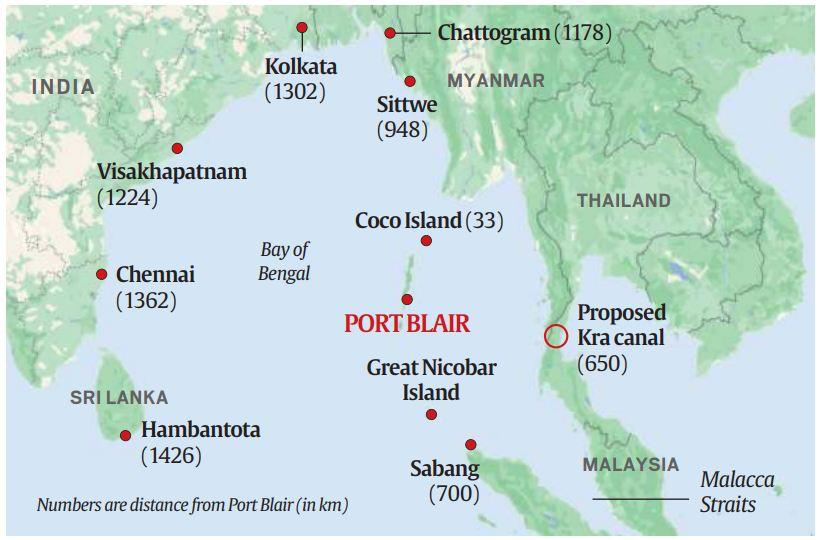

Recent disruptions in the Red Sea reveal a stark truth: India’s next major security challenge is likely to be maritime. For a peninsular country with three coasts, protecting sea lanes has become essential. Chinese naval, research, and survey vessels are increasingly active across the Indian Ocean, and Beijing has established footholds—most notably a long-term lease at Sri Lanka’s Hambantota, a significant port project in Myanmar, and reported surveillance activities near the Coco Islands just 55 km north of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Overall, this growing presence poses a strategic concern for New Delhi.

That is why the ANI are so important. Covering hundreds of islands, the chain extends from near Myanmar in the north to close to Indonesia in the south, bridging the gap between the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific. From here, India can monitor the Malacca Strait—the narrow passage through which a significant portion of China’s seaborne trade passes—thus addressing the core of Beijing’s “Malacca dilemma.” About 1,200 km from the mainland, ANI provide a forward base for persistent maritime patrols, humanitarian aid and disaster relief (HADR), and power projection across the eastern Indian Ocean.

Historically, concerns about ecology and tribal welfare, along with strategic caution, left this potential underutilised. Today, India is implementing a carefully calibrated, proactive plan to transform the islands into both an economic hub and a defence stronghold—arranging development to safeguard ecosystems and Indigenous rights while enhancing India’s influence across the Indian Ocean Region.

Indian Government Policy in ANI

India now pursues twin aims: to use the islands for geostrategy, trade, and sovereign presence—while safeguarding ecology and community interests. Security infrastructure is prioritised first, not because nature is considered expendable, but because credible power projection, faster HADR, and ongoing enforcement against illegal fishing, trafficking, and environmental crime depend on it.

Prioritising security isn’t a licence to override nature — it is a sequencing principle. Development is integrated into eco-zoning, seasonal work windows (e.g., outside turtle-nesting periods), and the preservation of biodiversity, alongside genuine community benefit-sharing. When approached in this manner, security and natural heritage mutually reinforce one another.

The Island Development Agency (established 1st June 2017) spearheads this initiative. Under its guidance, Great Nicobar Island (GNI) is being developed as a logistics and connectivity hub within the ANI chain. The plan is infrastructure-focused—a transhipment port at Galathea Bay, a greenfield international airport, a hybrid (gas-plus-solar, storage-backed) power system, and a compact support township—transforming a sparsely populated outpost into a shipping and services centre with spillovers for skills, tourism, and livelihood2s.

Location provides the strategic rationale. GNI is situated along east–west sea lanes and near three key chokepoints—Malacca, Sunda, and Lombok—positioning India alongside routes used by Chinese and other commercial and military vessels. Establishing a presence here allows for continuous maritime domain awareness, faster patrols, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) operations, and a credible maritime presence across the eastern Indian Ocean. Its proximity to Colombo, Port Klang, and Singapore enhances transhipment opportunities3. In brief, developing GNI is a strategically necessary move with significant economic benefits: it secures sea lanes, reduces logistical delays, and fosters growth. A well-planned, law-compliant approach safeguards biodiversity and preserves Indigenous rights.

The ANI Debate: Making of an Ecological Disaster in ANI

A long-standing tension underpins the GNI “holistic development” plan: infrastructure development versus the ecological security and livelihoods of Indigenous communities. Environmentalists, tribal rights advocates, and several political leaders warn of extensive forest loss, weakened legal safeguards, increased disaster risks, and inadequate due process, raising doubts about compensatory afforestation and emphasising risks to wildlife and the coastal zone4.

The social stakes are particularly high for the islands’ two tribes. The Shompen—a highly isolated, semi-nomadic community—are classified as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group; the 2011 Census recorded 229 individuals. The Nicobarese, a Scheduled Tribe spread across 19 Nicobar Islands, numbered 27,168 in 2011. Critics contend that the project could undermine cultural continuity, overburden health systems, and restrict access to traditional lands5.

Opposition has also been formal. In November 2022, the Tribal Council of Little and Great Nicobar rescinded its earlier “no-objection,” citing concerns over consent and clearances. Petitions before the National Green Tribunal and related reviews continue to scrutinise approvals. Meanwhile, academics and civil society groups urge a pause—or a complete reconsideration—until safeguards are demonstrably robust6.

In summary, advocates emphasise strategic value and potential gains; sceptics focus on environmental and tribal vulnerabilities. The decision now hinges on proof: precise data and oversight, enforceable safeguards, and genuine participation for affected communities.

Assessing the ANI ‘Disaster’ Narrative

Location Matters. GNI is situated beside the Six-Degree Channel at the western entrance to the Malacca Strait, one of the busiest shipping routes on the planet. India’s naval air station at Campbell Bay, INS Baaz, exists precisely for this reason: it “overlooks” the Malacca Strait and “dominates” the Six-Degree Channel, providing India with a forward vantage point on vital sea lanes and a launch pad for maritime patrol, surveillance, and disaster relief7.

Transform Position into Capability. Geography only matters if you can operate from it. The Great Nicobar plan’s core—a transhipment port at Galathea Bay, a greenfield international airport, dependable power, and a compact support township—is designed to turn distance into resilience: fuel, repair, airlift, and personnel on-island rather than occasional sorties from the mainland. That is the fundamental principle of island security8.

Economic Logic – Shorter Chains, Less Risk. Much of India’s east-bound and west-bound container traffic still transships at foreign hubs such as Colombo, Singapore and Port Klang, with roughly 3 million TEU a year handled offshore. A domestic node at Galathea Bay would cut detours and costs, retain value onshore, and reduce exposure to external policy shocks—while complementing, not replacing, mainland hubs like Vizhinjam and Kochi. The Union government has notified Galathea Bay as a “Major Port.” The rollout is phased and demand-led: about 4 million TEU initially, scaling towards 16 million TEU by mid-century as trade deepens9.

Enablers of Resilience. GNI is no longer just a digital outpost. Since August 2020, the Chennai–Andaman–Nicobar submarine fibre has provided high-capacity backhaul—2×200 Gbps on the Chennai–Port Blair segment—with onward links to outlying islands, including Campbell Bay. This supports command-and-control, telemedicine, education, and commerce. On energy, the islands are transitioning from diesel to renewable sources with storage. A 20 MW solar plant paired with an 8 MWh battery at Port Blair buffers weather disruptions, keeping traffic, hospitals, and port operations operational10.

Due Process and Oversight. Approvals for GNI were conditional: Stage-I Forest clearance (27th October 2022) and EC/CRZ clearance on 11 November 2022. In April 2023, the NGT formed a High-Powered Committee to revisit the identified gaps; the MoEFCC filed its report on 8 July 2025. This demonstrates democratic checks—conditional permits, tribunal oversight, monitoring—evidence of due process, not a preordained disaster11.

Indigenous Rights as the Legitimacy Foundation. Under the ANI (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, reserved areas and buffer zones restrict entry and limit commercial activity near tribal reserves. Project design must keep core interiors off-limits, enforce no-contact rules for PVTGs, and provide community-prioritised services—health, transport, telecom and market access.

Consent remains central: Gram Sabha/FRA pathways and MoEF circular practices, aligned with FPIC norms, should be integrated as ‘gate’ conditions during different phases. The goal is not to freeze the island in time; it is to co-design buffers and service corridors so essential infrastructure bypasses sensitive areas while vital services reach those who need them. Free, prior, and informed consent pathways and independent social audits can be incorporated as gate conditions for subsequent phases.

Ecology as a Design Constraint, Not an Afterthought. Great Nicobar’s leatherback beaches are globally significant. Galathea Bay’s west coast has long been a key nesting ground, with post-tsunami surveys confirming nesting resumed as beaches re-formed. That means any port or airport must embed proven turtle safeguards: downward-shielded, low-wavelength lighting; seasonal work windows; strict night-movement limits; noise caps; and full closures in peak nesting. Coral protection requires turbidity thresholds and time-bound dredging set away from high-value patches mapped in detail. Make “avoid–minimise–restore–offset” a measurable standard with long-term in-situ protection. These are not box-ticking exercises. They reduce life-cycle risk to the very assets we want to protect12.

Designing for Tsunamis and Storms. The 2004 tsunami serves as a warning, not a prohibition. India’s disaster management framework and NDMA tsunami guidelines emphasise risk-aware siting, raised plinths, enforceable setbacks, engineered drainage, sacrificial ground-floor elements, vertical refuges, and early-warning and evacuation protocols. Building according to modern standards now is safer than improvising later.

Redundancy near Malacca is a feature, not a bug. Mainland hubs—Vizhinjam and Kochi—are essential and expanding, but India still benefits from dual basing: a frontline node close to the chokepoint plus strong mainland ports. This distributes risk, reduces detours for east-bound trade, and significantly enhances HADR posture towards Southeast Asia when every minute counts.

What the Next Phases Should Lock in

- Security and the economy should remain the backbone. Port-airport-power-township phasing must be sustained, and demand-led ramp-up (≈4 MTEU initially, ≈16 MTEU in the long term) should continue; however, each phase must be conditional on meeting ecological and social criteria.

- Ensure transparency by default. Non-sensitive parts of the HPC assessment, monitoring data—such as turbidity, nest counts, and offsets—should be published on a rolling public dashboard.

- Tribal safeguards must be enforced effectively. Use PAT-Regulation zoning and no-contact rules; establish FPIC-style “free, prior, informed consent” pathways and independent social audits as prerequisites for subsequent stages; and direct benefits towards communities that genuinely request them.

- Ecology must be integrated as an engineering input. Ensure lock-in for turtle-safe lighting, work windows, dredging turbidity caps, and coral/mangrove buffers in the bid documents and EPC contracts, not just in reports.

- Climate-aware resilience. Increasing renewables lessens the diesel logistics tail.

Conclusion

The core message is that national security is not opposed to stewardship; it actually relies on it. A forward logistics hub at GNI enables India to deter coercion, protect shipping, and respond swiftly to disasters — all of which also help guard the marine environment from illegal fishing, trafficking, and pollution. The plan includes conditional clearances, tribunal-led reviews, and monitoring mechanisms. The right approach is prioritising security and the economy, with stewardship always in mind: build the backbone, set enforceable guardrails, and publish the scorecards. By following this approach, Great Nicobar can be both a frontline guardianship of maritime security and a model of responsible island development, rather than a warningary example.

- https://www.noaa.gov/blue-economy ↩︎

- MoEFCC clearance materials for the “Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island” and PIB notification ↩︎

- Dhristi IAS and https://maritimeindia.org/4132-2/?utm_source=chatgpt.com ↩︎

- National coastal body says Great Nicobar project no longer in prohibited zone, making way for a port, Simrin Sirur, 22 Aug 2024, Mongabay-India ↩︎

- PIB/Census 2011; secondary compilations ↩︎

- Tribals’ concerns on Great Nicobar project under examination, https://indianexpress.com/ 27 May 2025 ↩︎

- PIB, Ministry of Defence 31 July 2012 ↩︎

- Great Nicobar Project in spotlight: Why is it of strategic importance to India?, https://www.moneycontrol.com/ , 09 September 2025 ↩︎

- Great Nicobar Island Container Transhipment Port notified as major port, https://www.hindustantimes.com/ 05 August 2025 and PIB -Shipping and Waterways 2024, 31 December 2024.

↩︎ - Submarine OFC Connectivity to ANI, https://usof.gov.in/ and Andaman & Nicobar project: accelerating BESS deployment in India, https://etn.news/ 31 August 2020) ↩︎

- EC Identification No. – EC22A033AN125767 File No. – 10/17/2021-IA-III Date 11/11/2022 ↩︎

- First nesting record of leatherback sea turtles on the west coast of Galathea bay, after the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami , Shivbhadrasinh J. Jadeja1, Swapnali S. Gole, Deepak A. Apte, A Jabestin, https://iotn.org/ ↩︎

Add comment