All those who know something about the Mahabharata remember that the five Pandava princes were each given a domain, a prastha as part of the initial settlement with their cousins. Delhi lies within the boundaries of Yudhisthira’s Indraprastha, the central and most important one which retained critical strategic importance throughout the subsequent history of Bharat. From the accounts given in the Itihasa we understand that prasthas (the word implies stability, a dwelling place and a flat expanse) were self-governing, largely self-sufficient estates that included a capital city (pura) and villages within a network of roads and irrigation waterways. The concept and even the word survived all around the so-called ‘Indo-European’ civilisational area. In Greece the allegedly oldest city was Prataia or Platea in Attica, the origin of the English word ‘place’, and in medieval France the King ruled primarily his pré (translated in English as meadow), often called pré carré (square place), prado in Spanish and similar names in most Latin languages (from the Roman pratum), all from the Sanskritic/Indo-European verb root: Preh: to spread.

We can also look at derived concepts such as the ‘court’, which originally defined a square space, that originally meant a yard (courtyard) where the lord of the estate held ‘court’ and rendered justice (law court), and thus gave rise to the verb ‘courting’ for currying someone’s favour.

There is evidence that the prastha was an administrative, regal entity in many parts of ancient India and that the concept of a settled, well organised, defended, and delimited territorial unit within a mandala, such as the mandala formed by the five prasthas of the Pandavas between the Yamuna and the Saraswati, spread to other areas of Asia where the Bharatiya civilisation became dominant.

Angkor: the largest surviving Prastha

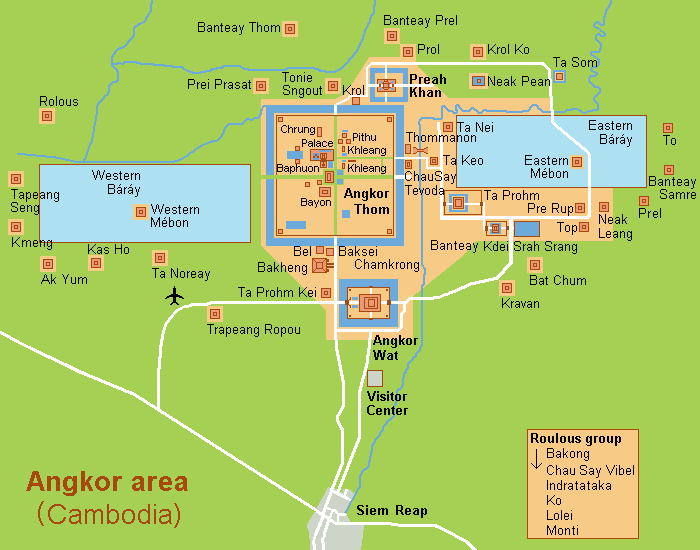

The largest currently identifiable site of that nature is at Angkor in Cambodia though there are many others in South and Southeast Asia. It has been discovered in the course of successive archaeological excavations and aerial mapping surveys that the urbanised area of Angkor was indeed immense and may have been the most populated metropolis on earth during the apogee of the Khmer Hindu-Buddhist empire several centuries ago.

As summarized in the google site, ‘Angkor stretched over about 3,000 square kilometres (1,200 square miles) at its peak’ (it was a quadrangle stretching more than 50 kilometres in length and breadth) . ‘The Angkor Archaeological Park, which includes the remains of the Khmer Empire’s capitals from the 9th to 15th century, covers about 400 square kilometres’. The Angkor Wat complex is regarded as the largest religious monument in the world, covering some 400 acres and ‘a 1,000 square kilometre hydraulic system was revealed in 2012 using airborne laser scanning technology’ (quoted from google AI).

In India the closest parallels that still exist are the great Southern temple-cities, such as Srirangam on the Kaveri.

Instead, the Khmer capital appears to have been a galaxy of townships separated by canals and barays (irrigation tanks) lined with forest patches, cultivated fields, and pastures that provided for the needs of the inhabitants. The seamless regular web of temples, palaces, monasteries, houses, water bodies, and fields evokes the topographic descriptions of janapadas and rajyas given in many epics and tales of ancient India and appears quite different from the structure of modern urban centres which, even when they are conceived as ‘garden cities’ only hold ornamental or recreational green areas whereas food and other necessities are produced in separate and often remote rural and industrial locations.

Like the Indian and Southeast Asian prasthas built as far East as Bali, Angkor is a tridimensional vishwamandala, (the dharmadhatu mandala was used later by Jayavarman VII to plan Angkor Thom and the Bayon temple) a microcosm built according to the instructions of the sulbashastras in the image of the Hindu-Buddhist symbolic universe, with the five-peaked Meru mountain at its heart, surrounded by water bodies and clusters of edifices that represent the oceans and continents of the physical earth.

The Smart Oasis Project

Is there a possibility in the modern world to draw inspiration from the prastha land-use planning? A large Luxembourg-based company headed by a Vietnamese-born French investor is implementing a related concept for human and infrastructural development in various countries, particularly in tropical and arid areas. The definition is that of a ‘smart oasis’. It is a self-sufficient domain in terms of (solar and alternative) energy production, water conservation and use, waste recycling, agro- and high tech industry, attractive residential planning and architecture, and efficient communication grids. The smart oasis can also focus on a core industrial activity suited to its environment and to the local skills of its dwellers. The promoters of the concept have identified several innovative, ecologically viable manufacturing processes such as the making of paper from limestone, of azolla fern through hydroponic cultivation (used as a natural fertilizer to replace chemical ones), of food from aquaculture and harvesting of sea or blue algae like spirulina, all suitably adapted to the geographical location and climate of the smart oasis.

The company that has developed the ‘smart oasis’ strategy has detailed budgetary and technical estimates for the creation of those new prasthas that are intended to improve the quality of life of their inhabitants while expanding the practice of agroforestry and other traditional and new methods and technologies. Significantly, the smart oasis concept is being promoted by the heir of a prominent Vietnamese business family steeped in the cultural traditions of the Indochinese sphere of influence that flourished for millennia along the Mahaganga or Mekong. India should be a pioneer in the use of this sustainable development strategy which can allow it to gradually redesign many of its rapidly- and chaotically- urbanising rural areas by combining the practical experience of the smart oasis designers with the prastha mapping principles.

The twin challenges India faces are the boundless growth of crowded megapolises fed by the immigration from the countryside and, in parallel, the haphazard mushrooming of semi-rural conglomerations that swallow many formerly agricultural communities without ensuring access to proper urban amenities such as proper roads, sewage, administration, and services. Prasthas or ‘smart oases’ can be planned at the State and district levels to manage and regulate demographic and economic transformation by inserting urban amenities within a preserved rural landscape.

An old French joke is about the impractical desirability of building cities in the countryside but, on the other hand a harmonious coexistence of human-scale agriculture with decentralised cityscapes is becoming more and more advisable in our times of climatic change and overpopulation, when digital electronic and AI technologies give many the option to work from home and will soon offer every household energy autonomy.

Add comment