Introduction

India is the seventh largest producer of coffee in the world, behind Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia, Ethiopia and Honduras. It produces 5.5 million bags of coffee a year and exports roughly 70 percent. Of the two coffee varieties – Arabica and Robusta – India grows 30 percent of the former.

Coffee is grown extensively in Southern India, which makes up the ‘traditional’ coffee growing areas. Since 1953 the Coffee Board of India has been experimenting with coffee cultivation in ‘non traditional’ areas, particularly the Northeast Region, and concentrated in Nagaland and Mizoram. The purpose of this article is to give an overview of coffee cultivation in Nagaland. Inputs on coffee cultivation were taken from interviews with two private players in Nagaland – Ete Coffee and Nagaland Coffee.

Coffee Cultivation in Nagaland

Nagaland’s volatile political history has stunted its economic growth. The state remains heavily reliant on its inherited resources, making agriculture important. Coffee cultivation in Nagaland began in the 1970s with the encouragement of the Coffee Board of India. The National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) was in charge of providing financial support for the programme, while the State Plantation Crops Development Corporation was in charge of the planting drive. Of the 40,000 Ha only 13,000 Ha was brought under coffee plantation, of which 7000 Ha was handed over to 5000 tribal growers.[1] In Nagaland, the project was carried out in partnership with the Nagaland Plantation Crops Development Corporation (NPCDC). Apart from encouraging coffee cultivation in the region, one main feature was to discourage Jhum (slash-and-burn) practices, to help prevent soil degradation along the hill slopes, and to improve socio-economic conditions of the tribal groups.

Despite the region having appropriate climatic and soil conditions for growing coffee, the project did not mert with much success due to multiple reasons. Lack of financial support from state governments was a looming problem, as was the Coffee Board’s reliance on the state governments for execution without providing adequate training. Eventually, the tribal people abandoned the land given to them for both financial and economic reasons. The coffee plantations were also abandoned in 1991 due to political unrest and lack of “proper market linkages to sell the produce”.[2]

More recently, there has been an effort to revive coffee cultivation in the region under a Special Area Programme (SAP). Under this programme, growers are given subsidy for converting their land into or expanding existing coffee cultivation. In addition, seeds are supplied and growers are trained in coffee cultivation practices. 4,000 Ha were identified in Nagaland for the cultivation of coffee, of which 1,372.50 Ha of coffee was planted by 2005 under the SAP programme.[3] In 2014 the Coffee Board partnered with the Department of Land Resources to revive coffee plantations. In 2016, the Department of Land Resources distributed thirteen lakh coffee seedlings to farmers. At the state level, the Government of Nagaland in its ‘Nagaland Vision 2030’ stresses on the need to revive coffee plantations as well as expand coffee cultivation using a cluster approach, with an added objective of helping to “reduce the outflow of labour from rural areas”.[4] Nagaland produces twice as much Arabica as Robusta, however its productivity levels were still very low at less than 100 kilograms per hectare.

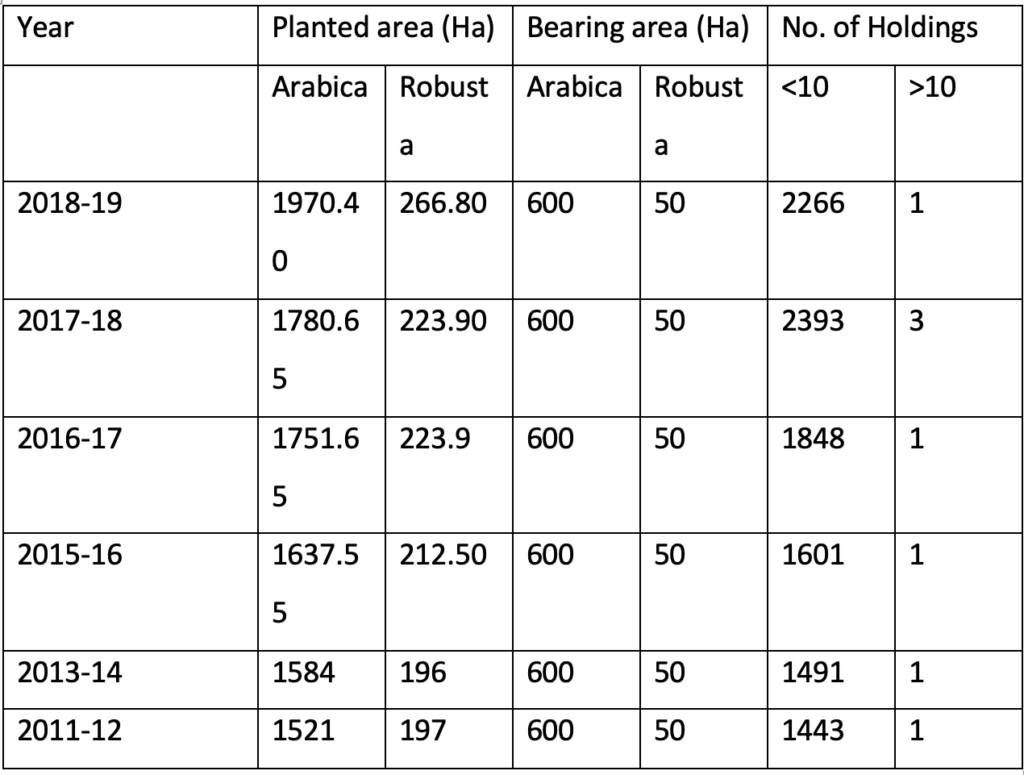

Table 1: Planted and bearing area of coffee in Nagaland

Source: Author’s own compilation of data from various Annual Reports of the Coffee Board of India

Challenges

Nagaland’s economy is characterised by infrastructure challenges, undeveloped local demand, and bleak opportunities for improving competitiveness through technical innovation within the supply chain. Some challenges are listed below:

- Resources

The state suffers from lack of manpower as most locals opt for government jobs rather than agriculture. Within agriculture itself, coffee ranks low in priority due to the failure of the 1970s experiment. The plantations are small holdings making coffee cultivation unviable. Coffee requires large investment which may not be possible for small tribal growers.

- Technology

There is inadequate adoption of technology in Nagaland’s coffee plantations from bean to cup. Moreover, there are inadequate processing and marketing facilities available.

- Accessibility

Nagaland is a landlocked state with a hilly terrain. Air, rail and road transportation systems are limited. This makes transporting coffee even within India a challenge. Private coffee companies face challenges with courier services who are slow given the difficult terrain. The longer it takes for coffee to be transported, the more its flavour weakens.

- Demand and supply

Considerable demand for Nagaland coffee exists in India and abroad. However, there is a lack of sufficient supply of coffee beans. Locals have not yet taken fully to coffee cultivation given their previous failures in the 1970s. Private coffee companies are finding it difficult to source adequate quantities of coffee beans to meet demands.

- Support

There are challenges in on-boarding new growers as well as reluctance among entrepreneurs to establish coffee-related businesses in Nagaland.

- International market

Coffee suffers from price volatility in the international market due to weather variables, long supply routes, and mismatch between demand and supply. It takes three-four years before a coffee plant can be harvested making it difficult to plan for short-term demand. Nagaland Coffee Private Limited is the sole exporter of Nagaland coffee. The company signed an MoU with the Government of Nagaland to distribute and export Nagaland coffee abroad. The company currently sells to the South African and Middle Eastern markets and has established a coffee shop in Cape Town. However, they face challenges in scaling due to the mismatch in supply and demand.

Recommendations

- Encourage expansion of coffee cultivation

Memories of the 1970s coffee cultivation experiment remain strong. This is hindering many families from adopting coffee cultivation again, despite its recent evident success. There is a need to advertise this success as well as provide monetary and emotional support and encouragement in adopting coffee cultivation.

- Capacity building

Through capacity building, either from the Coffee Board or the state authorities, coffee producers can become more profitable by growing and selling lucrative specialty coffee. Nagaland already has an inherent advantage as its climate and terrain is suited to grow only specialty coffee. Intensive capacity building may be provided in growing and processing coffee.

- Infrastructure support

Land-locked states like Nagaland have their own inherent challenges with infrastructure. The government is already working on improving this; however much more is left to be done. The only way by which coffee can become viable is when transporting it to storing facilities and eventually to the cupper and consumer is efficient and affordable.

- Encourage consolidation of holdings

The state authorities can learn from Nicaragua and El Salvador where coffee producer groups were established to overcome the challenge of smallholder coffee. In El Salvador, it was found that between 2008 and 2011, consolidation of holdings led to increasing incomes for farmers. It is also easier to implement innovative production and processing methods, and technology when holdings are consolidated. An added benefit is the standardisation of quality of production. Eventually, Nagaland could move towards a cooperative system for coffee that is most beneficial to growers.

- Assist in technology adaptation

Training can be given in traceability and quality management systems which are relatively easy and cheap technology to adopt. Coffee plants are sensitive to weather fluctuations which is a challenge in Nagaland. Technology exists to predict weather fluctuations and are specific to coffee plants. Such technology must be adopted. Tech-based agricultural innovations allow coffee growers to capture critical data points that can increase productivity and profit.

- Market support

One of the most traded food and beverage commodities in the world by volume is coffee. This market is currently unexploited. Post-harvest production is equally important to production. Direct commercial tie-ups with farmers is another option. Locals can be trained in coffee cupping and in marketing techniques. Nagaland coffee is mostly Arabica, organic, tribal-grown specialty coffee which automatically demands higher prices in the international market. This needs to be exploited.

[1] Rau, Krishna G V. “Coffee in North Eastern Region”. Coffee Board of India. 09 March 2007. https://mdoner.gov.in/contentimages/files/8_1.pdf

[2] Moa, Limasenla and Chakraborty, Sudip. A Study on Coffee Production in Nagaland. International Journal of Innovations in Management, Engineering and Sciences. 2 August 2020. http://www.ijimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/7.pdf

[3] Deka, Aniruddha. Plantation Development in North East India: Constraints and Strategies. Keynote Address at the National Conference on Economic Development of Assam, http://dlkkhsou.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/140/1/KN3.pdf

[4] Government of Nagaland. Nagaland Vision 2030. https://cdn.s3waas.gov.in/s368264bdb65b97eeae6788aa3348e553c/uploads/2018/04/2018042923.pdf

As the admin of this web site is working, no question very quickly it will be famous, due to

its quality contents.