Just last month at Dholera’s barren salt flats, excavators rumbled where, a year ago, there was only scrubland. By 2026 this will be India’s first modern 300-mm wafer fab, a ₹91,000-crore project led by Tata Electronics in collaboration with Taiwan’s Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (PSMC) that plans to push 50000 wafers a month off its lines and ship automotive-grade logic chips to customers the world over under the India Semiconductor Mission (ISM). 2,500 kilometres to the east, bamboo groves outside Jagiroad in Assam are being cleared for Tata’s ₹27,000-crore assembly-and-test unit. Scheduled to roll out 4.83 crore packaged chips every day by 2026, the plant will deploy home-grown wire-bond, flip-chip and integrated system-in-package technologies and is projected to generate about 15,000 direct and a further 11–13 thousand indirect jobs. The groundbreaking in the past few months was not only a corporate milestone; it was the clearest proof yet that New Delhi’s semiconductor gamble, dismissed by sceptics as PowerPoint industrialism, has crossed the point of no return.

India’s long association with chips has largely been cerebral. Roughly a fifth of the planet’s integrated-circuit design workforce sits in Bengaluru, Noida and Hyderabad, writing RTL code for everyone from Qualcomm to Apple, but the wafers those designs run on have so far come from foundries in Taiwan, South Korea or the United States. The COVID-era chip crunch and an increasingly weaponised technology trade made that bifurcation untenable.

The policy answer to this problem landed in December 2021. The Semicon India Programme put ₹76 000 crore on the table, half as direct cap-ex support for fabs and display plants, the balance for compound semiconductors, Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test (OSAT) lines and design start-ups, turning the state from cheerleader to limited partner in every part of the value chain. It was the largest single industrial incentive India had ever announced, and it came with another innovation: a dedicated India Semiconductor Mission to vet projects, release funds and keep day-to-day politics at arm’s length.

Nine months later the scheme was tweaked in a way only insiders fully appreciate. Instead of offering 50 % aid for advanced 28 nm chips and dropping to 30 % for older 65 nm ones, the revised rules from September 2022 give a flat 50 % subsidy on any chip plant, no matter the technology or material. That single stroke suddenly made India competitive for “mature” 40- and 55-nm lines that drive cars, telecom gear and power electronics, exactly the segments global majors wanted to diversify out of China.

Armed with cash and clarity, the Modi Government began to court technology partners the way it once wooed oil suppliers. The United States signed a bilateral semiconductor supply-chain partnership in March 2023; Japan followed with tool-maker tie-ups; and Taipei quietly agreed to industry-to-industry forums even without formal diplomatic ties. Inside India, the Semiconductor Mission became the single window that chip executives say Shenzhen once had and Washington still lacks. States competed too, Gujarat’s “Semicon City” policy underwrote land and electricity, while Assam’s tax holidays lured Tata’s massive OSAT project east of the Chicken Neck.

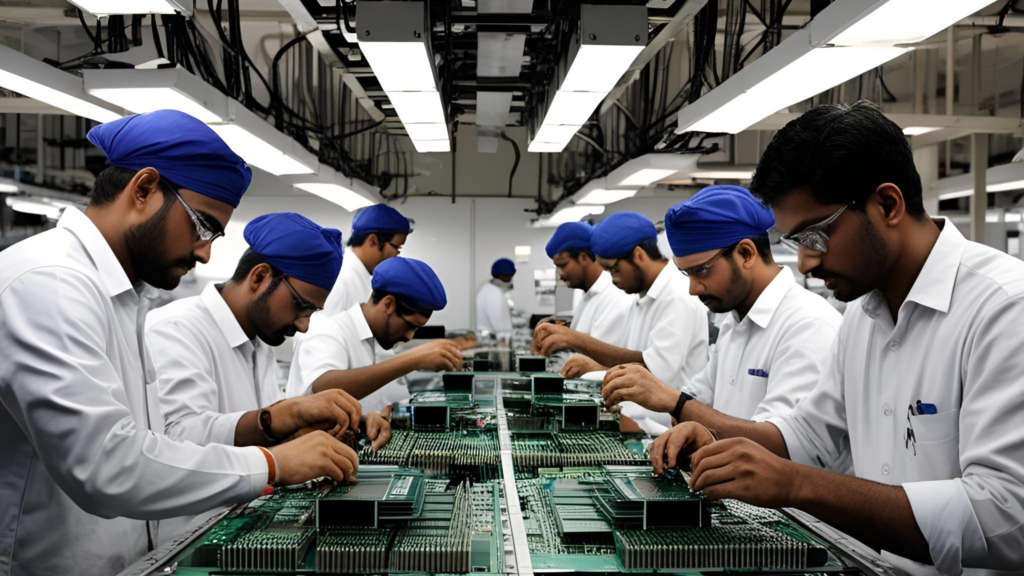

The results came fast. Tata-PSMC’s fab is the headline, but the Ministry of Electronics has cleared four other units in barely eighteen months. Micron’s $2.75-billion Assembly, Testing, Marking, and Packaging (ATMP) plant in Sanand, approved during Prime Minister Modi’s state visit to Washington, broke ground within 90 days; the company expects 5000 direct and 15000 community jobs once phase one opens in 2025. Together with Tata’s Assam line and the Renesas-backed CG Power facility next door, India will have the back-end capacity to package nearly seven crore chips a day before the end of the decade.

To critics who say India is merely bolting packages onto imported silicon, Dholera offers a counter-narrative: a front-end fab on day one, not year ten, and a Taiwanese partner bringing process IP that took Hsinchu decades to perfect. Powerchip is hardly TSMC, but it runs six fabs of its own and understands the brutal discipline of yield learning. For New Delhi, this is exactly the sweet spot, advanced enough to matter, mature enough to be politically feasible, and it sends a clear diplomatic message that Taiwanese industry is ready to shift some of its production risk away from China and into India.

The ecosystem is also being wired into India’s strategic circuitry. The government has earmarked more than a billion dollars to modernise the 1980s-era Semiconductor Laboratory in Mohali, taking it from 180 nm to 28 nm and ring-fencing production for space and defence payloads; DRDO, meanwhile, has announced indigenous GaN and SiC devices for next-generation AESA radars. For a military that still waits months for export permissions on radiation-hardened chips, a trusted domestic line is as valuable as a squadron of fighter jets.

Talent, India’s eternal comparative advantage, is getting its subsidy too. The Design-Linked Incentive promises to bankroll half the R&D costs of start-ups that tape out new silicon, while the Chips-to-Start-Up programme is piping VLSI syllabi into a hundred universities. Equipment giant Lam Research has layered a $150-million virtual-fab platform on top, pledging to train 60000 process engineers in the next decade, an engineer-a- month metric that dwarfs the size of Taiwan’s entire graduating cohort.

None of this will matter if the upstream pipe remains foreign. So Gujarat is fast-tracking permits for specialty-gas producers like Linde and Merck; INOX has already opened the nation’s first ultra-high-purity nitrous-oxide plant in Chennai; and the state’s investment bureau went a step further, opening an office in Taipei to court every tool, wafer and photo-resist supplier that feeds Powerchip back home. If India can lock in even a third of that ancillary spend, local value addition will compound far beyond the headline billions.

Setbacks have come, and loudly. Vedanta-Foxconn’s $19-billion joint venture collapsed when the Taiwanese side walked away citing the absence of a proven process technology partner. The episode was embarrassing, but it forced the Centre to insist on committed Tech IP before approving any new proposal, an early-stage correction most countries make only after years of sunk costs. Vedanta now claims to have lined up a fresh partner and re-filed its application; either way, the lesson has already been baked into the approval workflow.

The real stress test will come with the first wafers. Yields in a 28 nm line can bleed money at 85 percent and mint it at 92 percent; power outages, water salinity, even Gujarat’s alkaline dust storms can undo years of process optimisation; but it is precisely because of these uncertainties that the Modi government has chosen a policy of co-investment rather than arm’s-length incentives: when the state owns half the risk, it has skin enough to fix the grid, expand the canal network and, if needed, fly in ASML engineers at a moment’s notice. That level of political capital is hard to replicate in older democracies now wary of large-scale industrial policy.

Internationally, the semiconductor drive has become India’s new diplomatic calling card. Micron, Lam and Applied Materials arrived on the back of a U.S.–India supply-chain partnership inked at the White House; Japan’s Tokyo Electron has an equipment-supply pact with Tata; and the Taipei Times now runs editorials urging TSMC to view India as its “South-bound pivot”. Where earlier summits ended with boilerplate on climate and culture, they now close with announcements of fab clusters, training grants or tool-maker MoUs. Chip diplomacy, in short, is the new coal diplomacy.

Five years ago India had one ageing government fab and a diaspora designing chips for other nations. Today it has a funded front-end line, four large packaging plants under construction, a billion-dollar upgrade for its strategic foundry and a policy regime that pays for everything from photo-resist to PhDs. Execution risks remain, but the centre of gravity has already shifted: the question is no longer if chips can be made in India, but how many, and how soon. In the unforgiving semiconductor universe, that is the biggest jump in yield any country can hope for, and it has happened on Narendra Modi’s watch.

Add comment