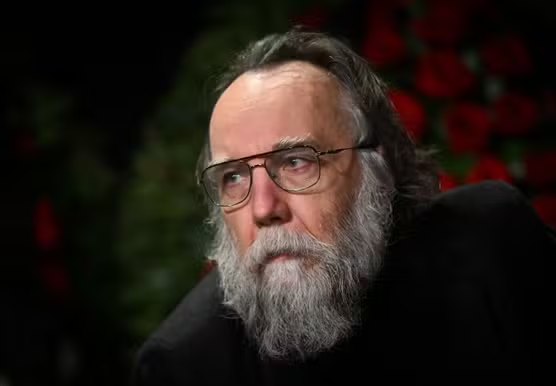

Meeting with Alexander Dugin, the famous philosopher and political scientist during his latest visit to Delhi the other day, confirmed my impression that he is a towering strategic visionary. Lean, bearded, eloquent, courteously aristocratic and yet accessible. Dugin, with a face that evokes a Renaissance depiction of a Greek sage, seems to belong to another age, perhaps the 19th Century which brought a multidisciplinary religious and cultural Renaissance to Russia. As the most influential geopolitical thinker of the last few decades in his native country, Dugin was internationally known even before he became tragically famous in the wake of the assassination of his daughter Darya by Ukrainian terrorists in 2022. His interview with Tucker Carlson last year was watched by millions. Though he is generally described as a spiritual nationalist, in the line of the Pan-Slavists of the late eighteen hundreds, he defines himself as a traditionalist and rejects nationalism in its narrow meaning because he believes in the broader concept of regional civilisations as defined by the late Samuel Huntington.

In Russia Alexander Dugin is an Eurasianist, an intellectual successor of Lev Gumilev but with a Christian Orthodox perspective in the line of Dostoyevsky and Ivan Ilyin. He is a leading voice against liberal woke leftism of the current Euro-American variety. Abroad he calls for and announces the onset of multipolarity between the leading civilisational states. He hails BRICS as the laboratory where the new global system is being built between States belonging to all continents and religious cultures. He emphasizes, like Putin and Lavrov who are reportedly influenced by his thought, that the new international system being developed within BRICS is not directed against anybody, not even against the USA and their NATO allies. It is instead a non-hegemonic structure that can eventually be enlarged to include the North American and European States. Dugin appropriately refers to the medieval allegory of King Arthur’s Graal-centric roundtable around which one seat was left empty for the knight still to come. There is no place for national or religious imperialism or expansionism in that worldview because it presupposes that all civilisations must be free to retain their cultural and socio-political characteristics and features and should not convert others to their customs, ways and beliefs. At the core of his doctrine is the rejection of cultural and ideological imperialism such as today’s globalism with its commitment to social engineering.

Dugin’s knowledge and understanding of Hindu spirituality and politics are impressive and his familiarity with Vedic scriptures, Vedanta and Buddhist texts, as well as with more modern Indian thinkers attests to his Eurasian spiritual mindset, very different from the attitude of most western social and political scientists, who are either agnostic about or dismissive of Asian ancient cultures. The Russian philosopher’s traditionalist convictions guide his evaluation of the Vedic social order that he describes as an interpretation of the natural law shaped by the specific geographic and historical environment of South Asia. In that light, he sees the wisdom of the varnashrama dharma (and of the Dharma the cosmic law) described by French anthropologist Louis Dumont in his seminal book Homo Hierarchicus. Dugin, like Dumont recognises the existence of diverse human types that require different treatment as they are called to perform different tasks. While making that assessment both the scholars argue that the authentic and sound varna system can only be based on personal dispositions and talent even though the socio-cultural environment and family traditions play a major role in determining individual characters and professions. The reality of social stratification, – whether we call its categories castes, like the Portuguese did in India or estates, as they were known in pre-Revolutionary Europe – is inescapable but must be tempered by the recognition of human freedom and continuous evolution. Dugin does not reject democracy but denies the desirability and even possibility of a uniform socio-political framework and system to be applied to all peoples and nations. A healthy democratic exercise must rely on a stable social fabric rooted in a metaphysically transcendent culture.

Like the perennial philosophers of the last century, Dugin denies that the abstract, utilitarian notion of a social contract provides a sufficient foundation for building and maintaining a civilisation. When he points out the paradoxes and aberrations of liberal ‘bourgeois’ democracy he echoes the Platonic and Aristotelian analysis of that system which sooner or later becomes corrupt and increasingly unsound.

The message that the Russian intellectual delivered during his visit to Delhi was related to his citation of Prime Minister Modi’s statement about the need for the mental decolonisation of Indians. Dugin argued that this process is needed in all formerly colonised countries (whether they were dominated politically or only intellectually). Russia too has to be decolonised according to him, and his action is intended to help bring about that transformation which Putin’s government supports by its internal and external policies. Dugin repeated more than once that the current ‘special operation’ is Ukraine is not a war between Russians and Ukrainians, who are interrelated and share a largely common history and culture, but rather a fight to defeat the advancing forces of hegemonic Western globalism that has turned the Ukrainian regime into its proxy against the Russkyi Mir, the Russian Slav orthodox world still largely untamed by Anglo-Saxon financial Leviathan.

In Dugin’s view India, that he hails as Bharat, is called to play a critical (a communist might say ‘epochal’) role in the worldwide transformation that is taking place towards multipolarity. He applauds the present government’s position of maintaining friendly ties with all countries, as far as possible, because it enables Bharat to maintain or build bridges and play a much needed mediatory role between nations and blocs. Unlike Westerners who tend to judge negatively the nation’s change of name ushered in by the BJP, Dugin hails it as a symbolic but essential sign of the nation’s return to its roots as a civilisational commonwealth. While pleading for a revival of the triangular RIC equation between Russia, India and China envisioned by the late scholar-statesman Evgeny Primakov, he also promotes the seemingly improbable but appealing prospect of another dialogue triangle for cooperation between India, the United States and Russia that would go a long way towards the prevention of a world war.

For this remote vision to become reality Dugin pins his hope on upcoming president Donald Trump whom he sees as an idiosyncratic traditionalist in the American context, heralding a return to the original ideals of the United States spelled out by Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, Adams, Lincoln and perhaps Andrew Jackson.

There certainly are a few questionable assertions in the message delivered by Alexander Dugin. His advocacy of civilisational states implies that countries sharing the same heritage should subordinate their national sovereignty to the larger interest of the geo-cultural community they belong to and we see how far this is from happening in the “Greater India’ that is South Asia. Dugin is right to distrust narrow nationalism but have regional coordination projects been successful, whether in Europe, Southeast Asia or Latin America which all are distinct civilisational entities, over and above their inner diversities? His belief that the USA under Donald Trump can become an equal partner in the new multipolar world sounds rather utopian from one who invokes geopolitical realism as his beacon. American nationalism is laced with exceptionalism and even if Trump sees it differently, he is unlikely to durably modify the hegemonic mindset of GOP politicians (and of the Democratic Party leaders as well) and leading US thinktankers.

Dugin is lucid when he defines nationalism as a dangerous ideology for multicultural states like Russia, India and Indonesia among others because the multitude of ethno-religious and linguistic communities that form those countries can become a cause of disintegration, just as it was for the German and Austro-Hungarian empires of yore.

Yet Dugin’s deep understanding of Bharat’s essential identity and his recognition of the country’s unique contribution to humanity make him a prophetic figure when he upholds a trans-religious spirituality that can, if not bring about the seemingly unachievable world peace, at least provide a required forum for the facilitation of understanding and harmony.

Add comment